A data-driven analysis of elected positions and democratic participation.

Dylan Foley

[[Written with Claude AI : Figures may be wonky but you get the idea, just dont quote this in your thesis]]

The Shock Factor

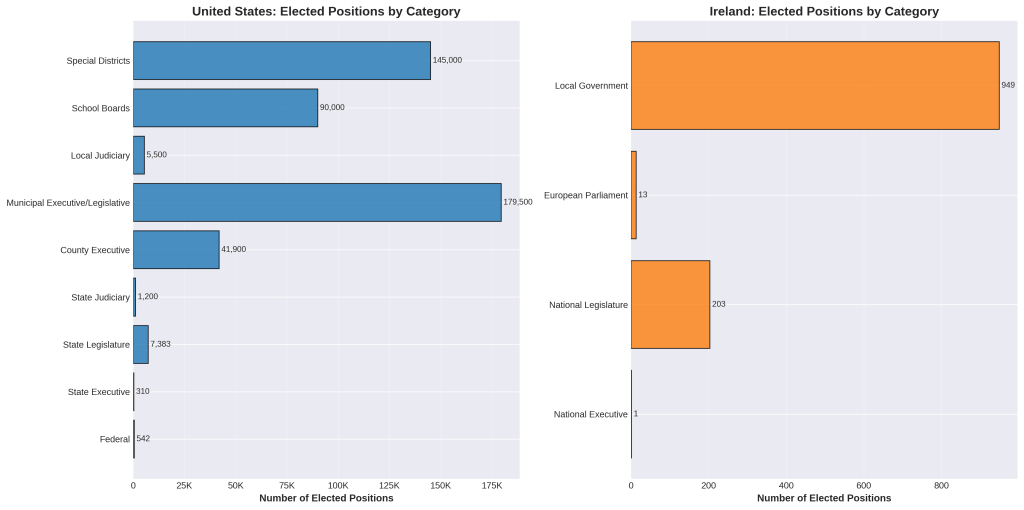

The United States has 471,335 elected positions across federal, state, county, municipal, and special district governments. Ireland has 1,166.

But this isn’t just about total numbers—the per capita difference is stark:

Ratio: Texas has 5.3x more representation per capita

If Ireland matched US levels of democratic participation, it would need 7,175 elected positions instead of 1,166—an increase of 515%.

For a country where 17% of the population is foreign-born—among the highest in Europe—this creates a profound question: What does it mean

for social mobility and integration when the democratic ladder has most of its rungs missing?

United States: 140.7 elected officials per 100,000 people

Ireland: 22.9 elected officials per 100,000 people

Ratio: The US has 6.2x more democratic representation per capita

Put another way: In the US, there’s one elected official for every 711 people. In Ireland, there’s one elected official for every 4,374 people

meaning each Irish elected official must represent 6.2 times more constituents.

Even Texas alone, a single US state, provides more democratic access per person:

Texas: 121.7 elected officials per 100,000 people (36,508 total positions)

Ireland: 22.9 elected officials per 100,000 people (1,166 total positions)

The stark difference in the number of elected officials per capita points directly to several structural features that can be framed as a lack of democratic inclusion and accountability.

1. Extreme Centralization of Power

- Ireland: As a unitary state, almost all significant political power is concentrated in the Dáil (the lower house of parliament) in Dublin. Major policy decisions—from healthcare and education to transport and planning—are primarily made at the national level.

- Implication: Local communities have very limited formal power to shape the policies that affect them most directly. They must lobby national politicians (TDs) to intervene in local affairs, rather than holding local elected officials accountable for local outcomes.

2. Weak Local Government with Limited Powers

- Ireland: Local authorities (county/city councils) have severely constrained functions. They are primarily responsible for local roads, housing, planning, and libraries, but their funding and policy mandates are heavily controlled by the central government. Key areas like police, justice, and education are entirely national.

- Comparison: In the U.S., states, counties, and cities have significant “home rule” authority. They can levy taxes, set education standards, and create laws on a wide range of issues. This creates a need for many more elected officials to be accountable for these separate spheres of power.

- Implication: Irish councillors have little power to actually govern their localities. This leads to a phenomenon where councillors often act as “caseworkers” or facilitators between their constituents and the distant central government, rather than as local legislators setting a unique local vision.

3. Lack of Direct Executive Accountability

- Ireland: The executive branch at the local level is not elected. The day-to-day administration is run by a non-elected, professional Chief Executive (formerly the County Manager), who is appointed by the national Public Appointments Service.

- Comparison: In the U.S., citizens directly elect a long list of executive officials—from Governors and Mayors to Sheriffs, District Attorneys, and Treasurers. This creates multiple, direct lines of accountability. If you don’t like what the Sheriff is doing, you can vote them out.

- Implication: In Ireland, there is no direct democratic mechanism to hold the local administration accountable. You cannot vote out the Chief Executive. This creates a “democratic gap” where significant administrative power is insulated from the ballot box.

4. The “Nationalization” of Local Politics

- Because local government is so weak, local elections in Ireland often become a referendum on the national parties in power, rather than a genuine debate about local issues and the performance of local councillors. This further undermines local accountability.

The United States: Seven Tiers of Democratic Participation

American democracy distributes power through an extensive network of elected positions across multiple governmental levels. Here’s what

actually gets put to a vote:

- Federal Level (542 positions)

President & Vice President (2)

US Senators (100)

US Representatives (435)

Delegates & Resident Commissioner (5) - State Executive (≈310 positions across 50 states)

Governors (50)

Lieutenant Governors (45 states)

Attorneys General (43 states)

Secretaries of State (35 states)

State Treasurers (38 states)

State Auditors (25 states)

State Comptrollers (15 states)

Agriculture Commissioners (12 states)

Insurance Commissioners (11 states)

Education Commissioners (14 states)

Public Utility Commissioners (12 states)

Labor Commissioners, Land Commissioners, and others - State Legislature (7,383 positions)

State Senators (≈1,972)

State Representatives (≈5,411)All 50 states have bicameral legislatures (except Nebraska) - State & Local Judiciary (≈6,700 positions)

State Supreme Court Justices

Appellate Court Judges

Trial Court Judges

Municipal Court Judges

Justices of the Peace

Magistrates

Note: About 87% of states elect some judicial positions - County Government (≈41,900 positions across ~3,000 counties)

County Commissioners/Supervisors (≈19,000)

Sheriffs (≈3,000)

District Attorneys/Prosecutors (≈2,300)

County Clerks (≈2,500)

County Treasurers (≈2,000)

County Auditors (≈1,500)

County Assessors (≈1,800)

County Coroners (≈1,400)

County Recorders (≈1,200)

County Surveyors (≈800)

County Engineers (≈400)

Constables (≈5,000) - Municipal Government (≈179,500 positions across ~19,500 municipalities)

Mayors (≈19,500)

City Council Members (≈135,000)

City Clerks (≈15,000)

City Treasurers (≈8,000)

City Attorneys (≈2,000) - School Boards (≈90,000 positions)

School Board Members across ≈13,500 school districts

Local control of educational policy, budgets, and administration - Special Districts (≈145,000 positions across ~38,000 districts)

Water District Boards

Fire District Boards

Hospital District Boards

Library Boards

Park & Recreation Boards

Sanitation District Boards

Soil & Water Conservation Districts

Port Authority Commissioners

Transit Authority Boards

Cemetery District Boards

Mosquito Abatement Districts

Drainage Districts

And dozens of other specialized local governance bodies

Total US Elected Positions: 471,335

Elected Positions per 100,000 population: 140.7

Ireland: Two Tiers and a Lot of Empty Space

Ireland’s elected positions are concentrated in just a few categories:

- National Executive (1 position)

President (largely ceremonial, 7-year term) - National Legislature (203 positions)

TDs (Teachta Dála) in Dáil Éireann (160)Senators in Seanad Éireann (43 elected by restricted electorate, 17 appointed by Taoiseach) - European Parliament (13 positions)

MEPs (Members of European Parliament) - Local Government (949 positions)

County Councillors (31 councils)

City Councillors (included in county councils)

No separately elected mayors (mayors selected by councillors)

Total Ireland Elected Positions: 1,166

Elected Positions per 100,000 population: 22.9

What Doesn’t Get Elected in Ireland?

This is where the story gets revealing. Here are the five complete tiers that are entirely absent from Irish democratic participation:

❌ No Regional/State Government Layer

Ireland has no intermediate tier between national and local government. Unlike US states or German Länder, there are no regional executives or

legislatures.

The Regional Assembly Illusion:

Ireland does have “Regional Assemblies” (3 regions: Eastern & Midland, Southern, Northern & Western), but these are: – Not directly elected by citizens – Composed of county councillors who nominate themselves – Created primarily to meet EU requirements for regional structural fund administration – Possess minimal actual governance authority – Function more as administrative coordination bodies than democratic institutions

❌ No Elected County/Local Executives

While Ireland elects county councillors, the actual executive power rests with: – County/City Managers: Appointed by the Public Appointments

Service (centralised national appointment) – Managers often hold more de facto power than elected councils – Councils can make policy, but

implementation is through appointed executives – No elected mayors with executive authority (unlike US mayors) This creates a peculiar democratic deficit: even the tier that is elected has limited authority over actual governance.

❌ No Elected Judiciary

All Irish judges are appointed: – Appointed by the President on advice of the Government – Judicial Appointments Advisory Board recommends

candidates – No direct electoral accountability to communities – Contrast with US: sheriffs, district attorneys, and judges at multiple levels are elected

❌ No Elected Law Enforcement

An Garda Síochána (police): National force, all appointed

No elected sheriffs or police chiefs

No elected district attorneys or prosecutors

All law enforcement accountability is through appointed administrators

Contrast with US: ~3,000 elected sheriffs, ~2,300 elected district attorneys

❌ No Elected Education Governance

School Boards of Management: Appointed, not elected

Patron bodies (often Catholic Church) control many school appointments

Parents have representation but not electoral control

Department of Education centrally controls curriculum and policy

Contrast with US: ~90,000 elected school board members with local control

❌ No Special District Democracy

Ireland has no equivalent to US special districts: – No elected water boards – No elected hospital district boards – No elected library boards – No

elected fire district boards – No elected parks and recreation boards – All such services are administered by appointed county managers or

national agencies.

Part II: The Numbers Tell the Story

Head-to-Head Comparison

| Metric | United States | Ireland | Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Elected Positions | 471,335 | 1,166 | 404:1 |

| Population | 335,000,000 | 5,100,000 | 66:1 |

| Positions per 100K people | 140.7 | 22.9 | 6.2:1 |

| Number of Democratic Tiers | 7 | 2 | 3.5:1 |

| Entry-Level Positions | 414,500 | 949 | 437:1 |

| Positions per 100K (entry-level) | 123.7 | 18.6 | 6.6:1 |

Breakdown by Government Level

| Level | United States | Ireland | Gap |

|---|---|---|---|

| Federal/National | 542 | 217 | US +325 |

| State/Regional | 7,693 | 0 | US +7,693 |

| County Executive | 41,900 | 0 (appointed) | US +41,900 |

| Local Council | N/A (in county) | 949 | — |

| Municipal | 179,500 | 0 (included) | US +179,500 |

| Judiciary | 6,700 | 0 (appointed) | US +6,700 |

| Education | 90,000 | 0 (appointed) | US +90,000 |

| Special Districts | 145,000 | 0 | US +145,000 |

Even Texas Alone Dwarfs Ireland

| Entity | Elected Positions | Population | Per 100K |

|---|---|---|---|

| Texas (one state) | 36,508 | 30,000,000 | 121.7 |

| Ireland (entire nation) | 1,166 | 5,100,000 | 22.9 |

| Ratio | 31:1 | 6:1 | 5.3:1 |

Even accounting for population, Texas offers 5.3 times more democratic participation opportunities per capita than Ireland.

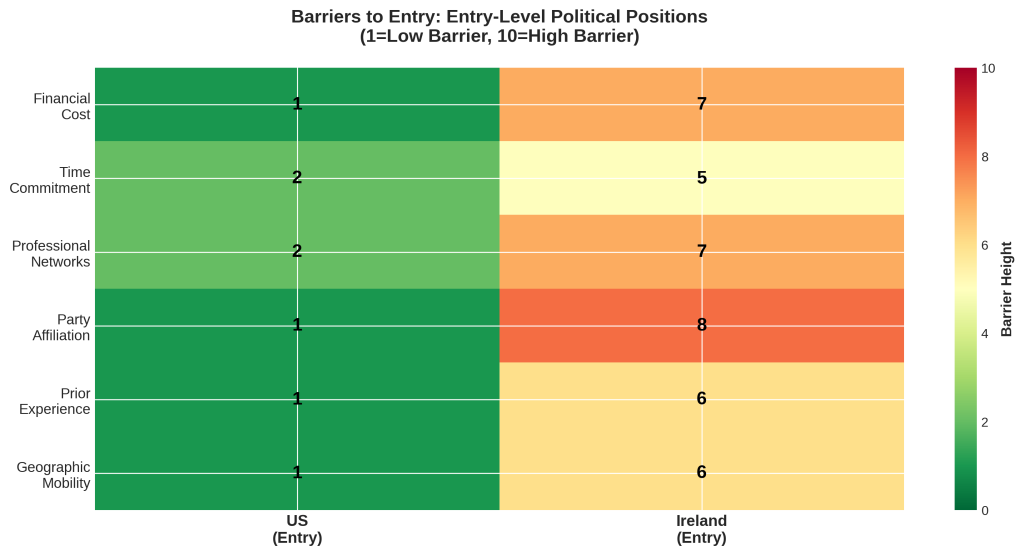

The Democratic Openness Index

To quantify these differences, I developed a Democratic Openness Index (DOI) based on six weighted factors:

| Factor | Weight | US Score | Ireland Score | Gap |

| Entry-Level Access | 25% | 9.5/10 | 3.0/10 | 6.5 |

| Pathway Diversity | 20% | 10.0/10 | 2.0/10 | 8.0 |

| Financial Barriers | 20% | 8.0/10 | 4.0/10 | 4.0 |

| Geographic Distribution | 15% | 10.0/10 | 5.0/10 | 5.0 |

| Party Independence | 10% | 9.0/10 | 2.0/10 | 7.0 |

| Representation Density | 10% | 9.0/10 | 4.0/10 | 5.0 |

| TOTAL DOI | 100% | 9.28/10 | 3.30/10 | 5.97 |

What This Means:

United States (9.28/10): Extremely open system with minimal barriers to entry, multiple pathways, geographic distribution, and party

independence.

Ireland (3.30/10): Moderately closed system with significant barriers, limited pathways, party dependence, and centralized power.

Gap (5.97 points): This enormous difference represents fundamentally different conceptions of democratic participation.

The Missing Ladder—Structural Implications

The Political Career Pathway Problem

In the United States, someone interested in politics can follow a gradual, four-tier ladder:

Tier 1: Entry Level (414,500 positions) – School Board Member: $500–$5,000 campaign cost, part-time, no experience required – City Council

Member: $2,000–$10,000 campaign, part-time, local connections sufficient – Special District Board: Often unopposed, volunteer work

Tier 2: Local Leadership (25,700 positions) – Mayor: $5,000–$50,000 campaign – County Commissioner: $10,000–$75,000 – Sheriff/DA: $25,000

$100,000

Tier 3: State Level (7,693 positions) – State Representative: $50,000–$300,000 – State Senator: $100,000–$500,000 – State Executive: $200,000

$2,000,000

Tier 4: Federal Level (542 positions) – US Representative: $500,000–$5,000,000 – US Senator: $5,000,000–$50,000,000+ – President: $50,000,000+

At each tier, skills and networks build incrementally. An 18-year-old can run for school board while working a day job. After proving themselves,

they can run for city council, then county commissioner, building credibility step by step.

Ireland’s Two-Tier System: The Steep Jump

Ireland offers only two meaningful tiers:

Tier 1: Local Council (949 positions) – County/City Councillor: €5,000–€20,000+ campaign – Requires: Party backing (usually essential), significant

time commitment – Power: Limited—county managers hold executive authority

[MASSIVE GAP—NO MIDDLE TIER]

Tier 2: National Legislature (203 positions) – TD (Dáil): €20,000–€100,000+ campaign – Senator: Various election colleges (43 elected by restricted

electorate) – Requires: Strong party machinery, national profile – Jump: From local council to national legislature is enormous

There is no middle tier. No state legislature to practice in. No regional executive to prove competence. The jump from having influence over your

local area’s roads and planning to voting on national budgets, foreign policy, and constitutional matters is one massive leap.

Who Pays the Price?—Social Mobility Impact

The structural differences between these systems don’t affect everyone equally. Certain groups face disproportionate disadvantages under

Ireland’s centralized, party-dominated model:

- New Citizens and Immigrants (+5 mobility levels disadvantage)

United States: – Immigrant arrives, gets involved in local school board meeting – Runs for school board after 1–2 years of residency – Wins

election within 2–4 years of arrival – Serves community while maintaining day job – Builds political resume for higher office

Ireland: – Immigrant arrives, joins political party (necessary step) – Spends years building party credentials – Seeks party backing for council

nomination (5–10 years) – Runs for council seat (10–15 years post-arrival) – Limited authority even if elected (manager holds power)

Impact: With 17% of Ireland’s population foreign-born (870,000 people as of 2024), this creates a massive integration bottleneck. The very

communities most in need of representation face the highest barriers. - Young People (+4 mobility levels disadvantage)

United States: – 18-year-old can run for school board immediately – Win local election by age 19–20 – Gain experience managing budgets, policies,

public meetings – Build track record for higher office by mid-20s

Ireland: – Young person joins party in late teens/early 20s – Spends years in party apprenticeship – May get council nomination in late 20s/early

30s (if connected) – First realistic elected position typically mid-30s

Impact: By the time an Irish young person reaches their first elected position, their US counterpart might already have 10–15 years of governance

experience. - Working Class Citizens (+3 mobility levels disadvantage)

United States: – Part-time school board or city council compatible with full-time job – Can serve community without leaving employment –

Campaign costs manageable ($500–$5,000) – No party machinery required

Ireland: – Council positions increasingly time-intensive – Higher campaign costs (€5,000–€20,000) – Party backing often requires years of unpaid

volunteer work – Manager system means less actual authority even when elected

Impact: Irish politics becomes increasingly professionalized and inaccessible to those without financial cushions or party patronage. - Geographic Minorities (+3 mobility levels disadvantage)

United States: – Can build entire political career in home community – No need to relocate for advancement – Local school board → County →

State can all be local

Ireland: – Political advancement often requires Dublin connections – National political career means Dáil in Dublin – Geographic concentration of

political power – Rural and regional voices filtered through party structures

Impact: Reinforces Dublin-centric power dynamics and weakens regional political autonomy. - Women with Family Commitments (+2 mobility levels disadvantage)

United States: – Part-time local positions compatible with childcare – Flexible school board/council meeting schedules – Can participate without

full-time political commitment – Gradual scaling of time investment

Ireland: – Even council positions demand significant time – Limited entry points mean higher competition – Party networking requires extensive

availability – Fewer positions = fewer opportunities

Impact: Despite gender quotas at national level, the lack of flexible entry-level positions reduces overall women’s participation. - Minority and Ethnic Communities (+2 mobility levels disadvantage)

United States: – Local majority communities can elect own representatives – School boards reflect neighborhood demographics – Pathway to

representation without party gatekeepingIreland: – Proportional representation helps at national level – But limited entry points and party control slow integration – Smaller communities

struggle to gain party nominations – No local positions to build ethnic community representation

Integration Velocity—The Timeline Problem

Perhaps the most striking difference is how fast a newcomer can meaningfully participate:

!– INTEGRATION TIMELINE TABLES –>US Timeline: Rapid Integration

| Stage | Timeline | Requirements |

|---|---|---|

| New Resident | Day 1 | None |

| First Participation | 1–6 months | Attend public meetings |

| Campaign Viable | 1–2 years | Community connections |

| First Elected Office | 2–4 years | Small campaign, local support |

| Mid-Level Position | 4–8 years | Track record |

| State/National Level | 8–15 years | State-level networks |

Ireland Timeline: Slow Integration

| Stage | Timeline | Requirements |

|---|---|---|

| New Resident | Day 1 | None |

| First Participation | 2–5 years | Party membership |

| Campaign Viable | 5–10 years | Party backing secured |

| First Elected Office | 10–15 years | Significant party support |

| Mid-Level Position | N/A | No such tier exists |

| National Level | 15–25 years | National party selection |

Integration Velocity Ratio: 3–5x faster in the US

Integration Timeline Comparison

| Stage | US Timeline | Ireland Timeline | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| New Resident | Day 1 | Day 1 | Same |

| First Participation | 1–6 months | 2–5 years | 4–10x slower |

| Campaign Viable | 1–2 years | 5–10 years | 3–5x slower |

| First Elected Office | 2–4 years | 10–15 years | 3–5x slower |

| Mid-Level Position | 4–8 years | N/A (tier missing) | No equivalent |

| State/National Level | 8–15 years | 15–25 years | 2x slower |

| Stage | US Timeline | Ireland Timeline |

|---|---|---|

| New Resident | Day 1 | Day 1 |

| First Participation | 1–6 months (attend meetings) | 2–5 years (party membership) |

| Campaign Viable | 1–2 years (community connections) | 5–10 years (party backing) |

| First Elected Office | 2–4 years | 10–15 years |

| Mid-Level Position | 4–8 years (track record) | N/A – No tier exists |

| State/National Level | 8–15 years | 15–25 years |

Key Takeaway: Integration Velocity

- US: Immigrants can hold local office within 2–4 years

- Ireland: Typically requires 10–15 years and party machinery

- Impact: 3–5x faster integration in US system

- Critical difference: Ireland has no middle tier between local council and national parliament

For a nation with 870,000 foreign-born residents (17% of population—higher than the US at 14%), this slow integration pathway creates significant

social cohesion challenges.

The Power Question—Even What’s Elected Has Limited Authority

It’s not just about what gets elected—it’s about whether elected officials actually hold power.

The County/City Manager System

In Ireland, even elected councils operate under a dual executive model:

Elected Council: – Makes policy decisions – Approves budgets (in theory) – Represents constituents

Appointed County/City Manager: – Appointed by Public Appointments Service (national body) – Implements policy – Often controls budget

preparation – Manages all staff – Effectively holds executive authority

In practice, managers frequently have more real power than elected councillors. Councils can make recommendations, but implementation rests

with unelected executives appointed from Dublin.

Compare this to US mayors (elected, with executive authority) or county commissioners (elected, with executive and legislative authority

combined).

Regional Assemblies: Democracy by Delegation

Ireland’s three Regional Assemblies might appear to add another democratic tier, but:

Not directly elected by citizens

Composed of county councillors who nominate themselves to regional positions

Created primarily to satisfy EU structural fund requirements

Minimal actual governance authority\

Function more as coordination bodies than democratic institutions

This is “democracy by delegation”—citizens elect councillors, councillors elect themselves to regional positions, creating an indirect and diluted

form of representation designed more for EU compliance than meaningful governance.

: Implications and Conclusions

The Trade-Off: Professionalization vs. Participation

Ireland’s system reflects a European preference for: – Professionalized civil service over elected administrators – Centralized expertise over local

variation – Party discipline over independent representation – Appointed managers over elected executives

This model has advantages: – Professional administrators with technical expertise – Consistency of service across regions – Reduced corruption in

local government – Protection from populist capture of specialized functions

But it comes with profound costs:

- Severe Bottlenecks in Political Participation

With only 1,166 elected positions for 5.1 million people (22.9 per 100K), Ireland creates artificial scarcity in democratic participation. This

concentrates political power among those who can navigate party structures and afford the time and money for limited positions.

- Delayed Integration of New Communities

For a country experiencing significant immigration (870,000 foreign-born residents), the 10–15 year timeline to first elected office means entire

communities remain politically voiceless for a generation. The US timeline of 2–4 years enables much faster integration and community

representation. - Class-Based Filtering of Political Aspirants

When entry costs are high (€5,000–€20,000), party backing is essential, and time commitments are significant, politics becomes accessible

primarily to those with: – Financial resources or party patronage – Time to volunteer extensively in party structures – Professional/social networks

within party hierarchies

Working-class, immigrant, and young voices are systematically filtered out. - Geographic Concentration of Political Power

Without regional/state governance, all significant political decisions flow through Dublin. Combined with party-dominated nomination processes,

this creates: – Dublin-centric policy priorities – Weakened regional political identities – Forced geographic mobility for political advancement –

Reduced responsiveness to regional concerns - The Missing “Practice Grounds” of Democracy

Perhaps most importantly, Ireland lacks the democratic practice grounds that the US provides in abundance. When an 18-year-old can run for

school board, they learn: – Public speaking and debate – Budget management – Policy implementation – Constituent service – Political compromise

The fundamental question is whether democracy is primarily about:

A. Participation (US model) – Maximum citizen involvement – Multiple entry points – Local control and variation – Direct accountability through

elections

B. Expertise (Ireland model) – Professional administration – Centralized consistency – Party discipline and coherence – Indirect accountability

through appointments

Ireland has chosen (B), but for a modern, diverse, rapidly-changing society, this choice creates increasing tension.

Questions for Ireland’s Future

As Ireland continues to evolve—with high immigration, growing diversity, urbanization, and generational change—several questions emerge:

Can 949 council seats adequately represent 5.1 million people?

That’s one councillor per 5,374 people. US local government averages one elected official per 700–800 people.

How does lack of democratic participation affect social cohesion?

With 17% foreign-born population, does slow political integration create parallel societies rather than integrated communities?

Does party gatekeeping limit innovation in governance?

When all entry requires party backing, do independent voices and new ideas get filtered out?

Should Ireland create an intermediate tier of regional government?

The gap between council and Dáil is enormous. Would elected regional governments help?

Could directly elected mayors with executive authority increase accountability?

Many European cities have moved toward elected mayors. Should Irish cities follow?

Is the appointed county manager system still appropriate?

In an era demanding democratic accountability, does it make sense for unelected officials to hold executive power?

Should education governance be democratized?

With declining church influence, is it time for elected school boards?

What about special districts for specific services?

Could elected water boards, library boards, or health boards increase local accountability?

: Methodology & Sources

Data Sources

United States: – US Census Bureau: Government Employment & Payroll Data – National Association of Counties (NACo) – National League of Cities

- National School Boards Association – US Census of Governments (2017, 2022) – State government official websites – Wikipedia: “List of state

executive officials” type pages

Ireland: – Central Statistics Office (CSO) – Department of Housing, Local Government and Heritage – Houses of the Oireachtas (Parliamentary

service) – Local Government Management Agency – Wikipedia: Irish government structure pages – Local authority websites

Estimation Methods

US Positions: – Federal and State: Exact counts from official sources – County: Estimated based on average positions per county (×3,143 counties) –

Municipal: Estimated based on average council sizes (×19,500 municipalities) – School Boards: Calculated from number of districts × average board

size –- Special Districts: Based on Census of Governments count of special districts (≈38,000) × average board size (5) –

- Judiciary: Based on state-by

state analysis of elected judicial positions

Ireland Positions: – Exact counts from official government sources – Councillor numbers from Local Government Management Agency – National

legislature from Houses of the Oireachtas

Limitations

US numbers are estimates for county, municipal, and special district positions. Actual numbers vary by state and locality.

“Elected” definitions vary: Some US judges are appointed then face retention elections. Some Irish positions have mixed selection

methods.

Not all positions have equal power: A US mosquito abatement board member and an Irish TD have vastly different authority.

Part-time vs. full-time: Many US positions are part-time volunteer; most Irish positions are professionalized.This analysis focuses on structure, not outcomes: More elected positions don’t automatically mean better governance.

Cultural context matters: US federalism and Irish centralization reflect different historical and cultural priorities.

Scope of Analysis

This analysis compares structural opportunities for democratic participation, not: – Quality of governance – Policy outcomes – Corruption levels- Citizen satisfaction – Economic performance

The purpose is to understand how different democratic structures affect access to political participation and social mobility through

democratic engagement.

Conclusion: The Democratic Architecture Matters

Democracy isn’t just about voting every few years—it’s about the architecture of participation. The structures we build determine who can

participate, how easily they can rise, and whose voices are heard.

The United States has built a hyper-democratic system with 471,335 entry points. Ireland has built a centralized system with 1,166. Neither is

inherently “better”—they represent different values and trade-offs.

But for Ireland, with its rapidly diversifying population, the question becomes urgent: Can a nation with just 949 local council seats and no

intermediate government tier provide adequate democratic participation for 5.1 million people in the 21st century?

The data suggests it’s worth asking.

by

Tags: