Dylan Foley – Archaeological SETI (Search for Extra-Terrestrial Intelligence) Philosophy of Archaeology Series

Words:1823

Time to read:10 minutes

We Know Exactly One Thing About SETI

In the search for extraterrestrial intelligence, we face a lot of uncertainties. Although we can make educated guesses, we don’t know if life commonly emerges on other worlds. We don’t know if intelligence typically evolves. We don’t know if technological civilizations endure or quickly self-destruct. But we know one thing with absolute certainty: right now, on this planet, a technological civilization exists and actively transmits signals into space.

This single fact reveals something profound that allows us to reframe both SETI and archaeology, and when we consider the timescales involved, the implications become clear and startling.

The Temporal Overlap Problem

Our galaxy is approximately ten billion years old. Technological civilizations, based on our only example, have existed for perhaps hundreds to thousands of years, possibly extending to tens of thousands if we’re fortunate. Even if technological life emerges regularly across the galaxy, the probability that two such civilizations exist simultaneously and within detectable range approaches zero, if, as seems likely, technologically advanced civilisations undermine their own ability to survive. We see from climate change to weapons that the bottleneck through which any reasonably advanced species must endure, is inevitable.

So, if technological windows are brief compared to galactic timescales, then at any given moment, there may be only one or two technological entities active in an entire galaxy. The minimum we know is possible is one, because we exist. But this minimum also suggests that when we search for alien signals, we’re almost certainly not searching for contemporary transmissions from currently active civilizations.

We’re searching for archaeological artifacts of extinct ones.

SETI as Time-Delayed Archaeology

This realisation inverts our understanding of what SETI actually does. The conventional framing treats SETI as a search for active communication from living civilisations, perhaps hoping for dialogue across the stars. But if temporal overlap is unlikely, then SETI is actually archaeology conducted at cosmic distances. We’re looking for traces, for signals that have outlasted their creators, for information preserved across timescales that dwarf human history.

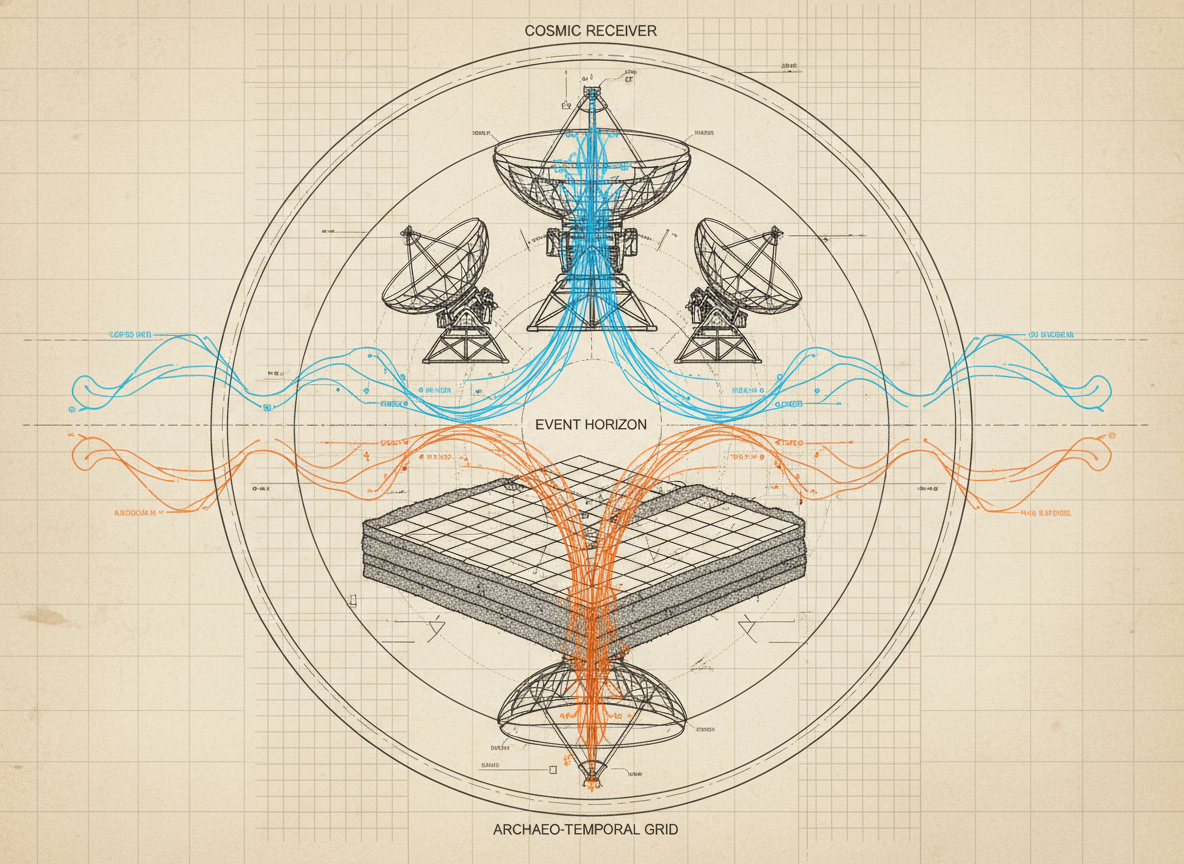

This makes SETI and terrestrial archaeology not merely analogous but fundamentally the same discipline applied in different spacetime directions. Archaeology recovers signals from entities separated from us by time. SETI searches for signals from entities separated from us by space. Both are exercises in detecting, interpreting, and reconstructing information from sources we cannot directly observe or communicate with.

The Unified Framework: Long-Distance Signal Science

If we accept this symmetry, then both disciplines are engaged in what we might call “long-distance signal science across spacetime.” The core challenges are identical in both fields. How do you detect intentional patterns against natural backgrounds? How do you interpret information without shared context or language? How do you distinguish artifact from accident, signal from noise, design from coincidence?

More importantly, if both disciplines face the same fundamental problem, they should inform each other directly rather than superficially. Archaeology isn’t merely analogous to SETI in the way that, say, forensics might provide useful metaphors. Instead, archaeological methodology is directly applicable to SETI, and SETI’s engineering concerns should directly shape archaeological practice.

The Preservation Imperative

Here’s where the framework becomes potentially transformative rather than merely descriptive. If SETI searches primarily find evidence of extinct civilizations, and if technological windows are brief, then any civilization with foresight faces an obvious imperative: preserve your planetary history in a form that can survive and remain interpretable across geological and cosmic timescales.

This isn’t just about ensuring your own descendants can access their history, though that’s valuable. It’s about recognizing that if you’re alone in your temporal window, your civilization might be the only one capable of encoding the story of your planet. Four billion years of evolutionary history, the emergence of life, the development of complexity, the appearance of intelligence—all of it vanishes unless someone preserves it before the window closes.

That someone might be us. And the window might be now.

Why This Matters for Archaeology

This reframing elevates archaeology from a discipline concerned with understanding the past for cultural or educational purposes to one with species-level importance. The archaeological reconstruction of Earth’s history isn’t just valuable for us; it may be our only opportunity to transmit that history to the deep future, whether the audience is our own distant descendants, future terrestrial intelligence that evolves after we’re gone, or alien archaeologists investigating what happened on this planet millions of years after we’ve vanished.

Every archaeological site excavated, every palaeontological fossil analyzed, every geological record interpreted becomes part of a dataset that we might encode and preserve. The urgency is real. Climate change, mass extinction, technological collapse, or simple erosion could eliminate both the archaeological record itself and our capacity to interpret it. We exist in a possibly unique window where we’re technologically advanced enough to attempt preservation while the record still exists and remains interpretable.

The Paradigm Gap: Why Archaeology Didn’t Engage in 2014

n 2014, Douglas Vakoch edited a NASA publication titled “Archaeology, Anthropology, and Interstellar Communication,” calling on archaeologists to contribute their expertise to SETI. The response from archaeology as a discipline was disappointingly sparse. Vakoch correctly understood that archaeologists work with traces of cultures distant from us in time and context, making their interpretive methods potentially valuable for thinking about communication with equally distant alien civilizations. The invitation was genuine and the reasoning sound from SETI’s perspective.

But archaeology as a discipline was fundamentally unable to engage with this opportunity, and the reason goes deeper than lack of interest or imagination. The vast majority of archaeological practice, even at its highest professional levels, operates within paradigms that are not coherent with physics. While archaeology has successfully incorporated some scientific methods—radiocarbon dating being the prime example—these typically arrive as extensions from natural sciences and engineering rather than emerging from archaeology’s own theoretical foundations. The underlying philosophy of archaeological interpretation remains largely divorced from the frameworks that govern SETI research: signal processing, information theory, physical causation, and mathematical formalization.

This isn’t a failure of individual archaeologists or even of Vakoch’s initiative. It’s a paradigm issue, an incompatibility in how the disciplines conceptualise their fundamental objects of study. SETI researchers think in terms of signals, transmission, detection, and information encoding because they work within frameworks derived from physics and engineering. Most archaeologists think in terms of culture, meaning, interpretation, and context because their discipline developed primarily within humanities and social science traditions. These are different languages, different epistemologies, different ways of understanding what counts as explanation.

Without a bridging framework that allows archaeology to reconceptualise its work in terms compatible with signal science, the disciplines simply talk past each other. Archaeologists hear invitations to speculate about alien culture and correctly recognize this as beyond their expertise. They don’t hear the deeper connection: that they’re already doing long-distance signal recovery and interpretation, just aimed at temporal rather than spatial distances.

The Research Reorientation

This doesn’t mean archaeology or SETI should abandon their current work. Archaeologists should absolutely continue reconstructing the past, because that reconstruction is the prerequisite for any preservation effort. SETI should continue searching for contemporary signals, because we might be wrong about temporal overlap, and the cost of missing a real contact would be enormous.

But both disciplines should recognize a deeper, unifying purpose: developing the science of long-distance signal transmission and detection across spacetime. Every archaeological excavation should ask not just “what happened here?” but also “what made this discoverable and interpretable to us, and how could we apply those principles to preserve our own record?” Every SETI search should consider not just active transmissions but also passive artifacts, durable structures, and encoding strategies optimized for discovery across geological rather than historical timescales.

Multiple Futures, Same Solution

The beauty of this framework is that it remains valuable regardless of which future scenario unfolds. Perhaps we successfully navigate our technological challenges, and our descendants millions of years from now need to understand their deep history. Perhaps we don’t survive, but other intelligence eventually evolves on Earth and could benefit from knowing what came before. Perhaps aliens eventually investigate our solar system long after the Sun has expanded and consumed the inner planets. Perhaps we discover that others attempted the same preservation, and recognizing the patterns helps us find them.

In every scenario, the solution is the same: encode planetary history in the most durable, discoverable, and interpretable form possible. This gives both archaeology and SETI a concrete, achievable goal with existential importance. Because the attempt to figure out how to preseve and transit information into the far future will also inform us on what we should be looking for if such a thing already exists in the galaxy.

Practical Next Steps

The immediate research questions that emerge from this framework cut across multiple disciplines. What materials and encoding strategies survive millions of years in various planetary environments? How do you create self-interpreting information structures that remain meaningful without shared language or cultural context? What geometric and statistical patterns remain obviously artificial despite transformation over geological time? How do you design redundancy that ensures reconstruction despite massive data loss?

These aren’t abstract philosophical questions. They’re engineering problems with testable solutions. And we have a laboratory to test them: Earth’s own archaeological record. Everything we successfully recover from the past tells us something about what will be recoverable from our present. Every failed interpretation reveals encoding strategies that don’t survive the test of deep time.

Conclusion: A Science for Deep Time

We stand at a potentially unique moment in Earth’s history—technologically capable of attempting preservation while the record still exists to preserve. Whether anyone ever receives the transmission is unknowable. But the attempt itself is worthwhile, because if we’re right about temporal windows being brief and rare, then the alternative is that four billion years of planetary history simply vanishes, and no one ever knows it happened. Which may well be the fate of countless other planets with life in our galaxy, and the reason we encounter no signals as yet.

Archaeology and SETI, properly understood, are the same science: the detection and interpretation of signals across vast distances in spacetime. By making preservation the explicit goal of both, we create a framework that unifies these disciplines, justifies expanded research and funding, and ensures that if we’re alone in our window, we at least leave something behind for whoever comes after—whether that’s in a hundred years or a hundred million.

The universe is full of signals waiting to be found. We might be the only ones in a position to create them. That’s not just an opportunity. It’s a responsibility.

References

Tarter, J. (2001). The Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence (SETI). Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics, 39(1), 511-548.

Kuhn, T.S. (1962). The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. University of Chicago Press.

Vakoch, D.A. (Ed.) (2014). Archaeology, Anthropology, and Interstellar Communication. NASA Office of Communications, Public Outreach Division.

Foley, D Furey, E (2025). From Geospatial Patterns to Ancient Signals: A

Signal Based Framework for Archaeological Machine Learning. ISSC Conference Proceedings 2025.