& The Case of The Iron Deadlight

4,485 words, 24 minutes read time.

Contents

How Sligo is losing its built heritage, residential, commercial and industrial. The Council is forcing the demolition of 5,6,7,8,9 High Street, but with no mention of the loss of street frontages in the Old Town area of Sligo.

The council and the preservation laws are facilitating, albeit inadvertently, the steady loss of the old town urban fabric. Many iconic shop fronts, residential and industrial buildings, cobbled streets, mills and weirs, have been lost over the years, a legacy that does not seem to be changing.

Because of a lack of funding, infrastructure and expertise for councils heritage operations, the same laws intended to protect heritage are ironically leading to its loss,

— Here is a real case study of how it happens.

Introduction

In 2019 a building was demolished at 39 High Street Sligo and the site cleared. The building had been declared dangerous, and the council, using the Local Government (Sanitary Services) Act 1964, prosecuted the owners to demolish the site. The councils executive arm moved in to demolish the site in 2018.

There were some issues with this though, as it was in 2016 that this building was listed as a cndidate for inclusion on the Record of Protected Structures (RPS), a list that the elected council can vote buildings on or off, and one of the few powers still in the hands of elected councils. Shortly after the recommendation members of the council moved to have it declared unsafe.

Secondly, the facade at least of most of the buildings in the old part of town are supposed to be kept where possible because of their unique and irreplacable character. This is set out in the councils own planning and heritage guidelines. There is no evidence in public information that any attempt to preserve the facade was made.

Lastly, and perhaps most importantly, 39 High Street was not just one building. Two buildings stood on the site. The one that fronted to the street which was the subject of the demolition order, and a second old stone building to the rear, that had been accessible from the Market Yard and Walkers Row, (now Dominic Street). The two were joined by a long ground floor extension that made the site appear as one structure. The second building was cleared without a proper understanding of its history.

This article highlights these issues, and looks at the use of the Sanitary Services laws by the council and building owners in order to clear sites for development.

The question is not whether buildings should ever be demolished, as clearly they sometimes should be. But, the councils own guidelines are very clear on the importance of the preservation of the old street-scapes, recommending that every effort be made to preserve the facades at least. This is so even in cases where the rest of the building cannot be saved.

No effort to retain the facade at 39 High Street, despite recommendation from architectural conservation report to do so was made. The sequence of events leading to the demolition demonstrates precisely how heritage is lost in Sligo, and the large gap that exists in heritage services that should provide an integrated view of heritage protection in the town.

Where Was It?

Number 39 was within the Market Cross Architectural Conservation Area (ACA) as set out in the Sligo and Environs Development Plan. As it says in the The Sligo City Centre Action Plan in which it is stated it is the councils aim to “Protect and enhance Sligo’s character and heritage”.

The site was beside the Dominican Friary to the north. This building was erected in 1971. This site was not an ancient church site as the earlier 18th century Friary is several hundred metres to the south at Burton Street.

The building was proposed for protection by inclusion on the Record of Protected Structures (RPS) in 2016. But, before it could be placed on this protected list the building was demolished. In fact, its placement on the recommendation list for preservation of the facade appeared to hasten the intent to demolish it, Be that as it may, an historical architectural survey was carried out which recommended the retention of the facade. This report is not publicly available.

An aim which is in the councils own heritage guidelines.In a similar manner with the present demolition of No.s 5,6,7,8,9 High street on the opposite west side of the road from 39, there has been, again, no public mention from councillors, county heritage officers or anybody else, of any attempts to preserve the facades at a minimum.

High Street in the Nineteenth Century

High St. was a busy commercial district of the town from the late 17th century until its decline after the mid 20th century. The focus of commercial activity has gradually moved to the lower ground to the north on O Connell street, but from the 17th to 19th century this was the main route into town from the southern roads at Gallows hill and Old Pound street.

High St. and its lower section Market Street are at the centre of what can be termed the Old Town district, an area running from the medieval friary at the east edge of the town along the higher ground near the courthouse and towards the cathedral of St John the Baptist on John Street. The quarters of the town (there was no “Italian Quarter a recent commercial invention) are the Abbey Quarter, the Castle Quarter and the Rath Quarter to the north.

A new market place was laid out to the west of High Street in the early 1720s, which became known as the Market Yard. The gated yard received heavy cart traffic from Sligos hinterland and further afield, which was directed into the weighbridges and customs pounds in the area. When goods were released after duty being paid, they were sold on the stalls or to merchants for onward shipping. Around the yard there developed small industries based on manufacturing products from these materials. Workshops and factories gradually surrounded the yard.

Several of these warehouses and factories were connected to shop premises that fronted onto the street, so that goods made in the rear were sold at the front. In this way we see the Victorian supply chain in action from the arrival of goods carts with materials and food etc to the processing and manufacture of objects from these materials and the selling of goods from the retail premises that fronted onto the streets, in particular the busy High Street.

The front building served for a long time as a retail business, A list of some of the proprieters is below.

Number 40 had served as a post office in the 19th century.

- 1839 the site operated as a tinsmith at this time run by a William White.

- 1881 Elizabeth Cahill ran a general store offering seed & guano merchant, a bookseller and stationer, leather seller and ironmonger.

- In 1889 the premises was occupied by a William Ormsby Hunt who had moved from Bridge street and replaced a James Cahill

- 1894 William O. Hunt still ran an Ironmongers, selling paint, roompaper, glass and leather.

- 1902 A P J McCarrick operated a bakery from this premises

- Thomas Mostyn followed by Greene & McNiece, both businesses sold horse drawn agricultural machinery, such as hay mowers.

- The site operated as Roches furniture store until the 1970s

The old Friary (pictured above) on this location was built in 1848 and demolished in 1971 and the property at number 40 was also demolished at this time. An ornate section of the old friary church still exists to the rear of the modern friary.

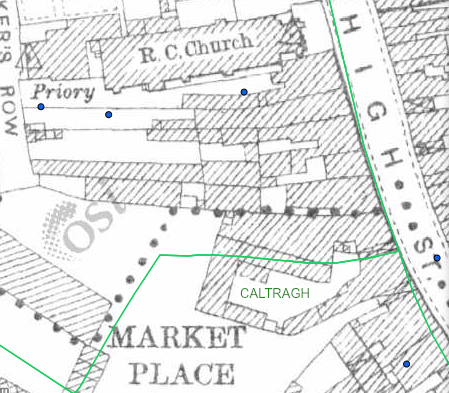

Below the building to the rear of No. 39 is marked by a black square

Judging by the old maps, it seems quite possible that the building at the rear was already in existence as far back as the 1837 OS surveys.

The Second Building

The rear building was a strange mixture of stone and red brick and concrete block patching, a lot of which was in poor condition. The first floor shows features of a late 19th / early 20th century store or workshop. Dual pitched roof contained to larhe roof-lights illuminating a first floor space.

The ceiling consists of tongue and groove boards fixed to the rafters with rows of nails. The date of these is uncertain but are unlikely to be earlier than 1890, based on the fact these were machine cut from this time. There was the remains of a red brick arched doorway at the rear of this building, which either represented a loading dock or led to a since demolished building attached.

There was a hoist evident to the south side of the building for raising loads to this floor.

The floor was in poor condition which precluded walking on it.

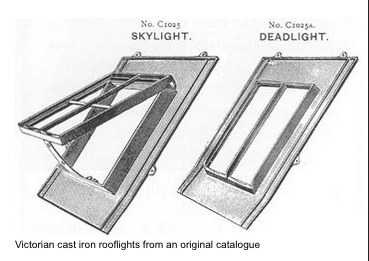

It is possible the two large roof-lights may be a feature of the old roof. These roof-lights are a feature of mid to late Victorian workshops and it is likely they date to this time. Just visible on the right hand roof-light is a glazing bar, dividing the glass in two, this is an authentic feature of Victorian roof-lights.

The roof shows extensive evidence of repair with doubling of ceiling joists and purlins. The battens holding the slates appear also to have been replaced in a patchy manner.

A Lost Technology: Passive Solar Lighting

The main historic interest resides in the two large cast iron roof-lights, These are a feature of workshops and factories prior to the widespread adoption of electricity to light such spaces in the early 20th century.

Once electricity came in around the turn of the 19th/20th century after Joseph Swan in Britain and Edison in the USA found the solution in 1879. They found that passing current through a fine carbon filament could produce light.

After this it was much cheaper to install a light-bulb and switch in stores and workshops, rather than the expense of overhead passive solar lighting.

Such lighting was usually north/south facing to maximise the indirect solar illumination throughout the day, preventing harsh shadows and direct sunlight.

It is likely these are installed sometime between 1880 and the early 1900s.

This form of natural lighting for buildings has been resurrected in the early 21st century after falling out of use for almost a hundred years with the introduction of electricity.

Offer more opportunities for natural light. Since vaulted ceilings create extra surface area on opposing walls, they offer additional space for large windows

Many vaulted ceilings follow the roof pitch, as this one does which means skylights can fit directly into the ceiling, in other words this room was designed from the start to be lit by the skylights.

On overcast days top-lighting is 3 to 10 times more effective than side lights.

The Factory and The Sligo Manufacturing Society

To get an idea of the type of manufacturing businesses working in the Market Yard, I have looked a sample in the records. The area functioned at the time in a similar way to how we would imagine an industrial estate. With supply vehicles coming into the yard from the main roads, raw materials distributed to the factories and workshops surrounding the yard, and then moving to the retail sections of buildings fronting the main streets.

In 1889 the Sligo Tweed Factory was opened in the “Market Square, High St.” by Cornelius McPake and Glendinning.

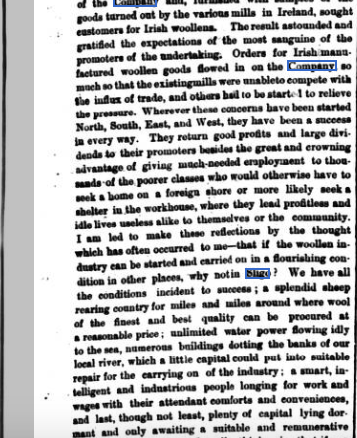

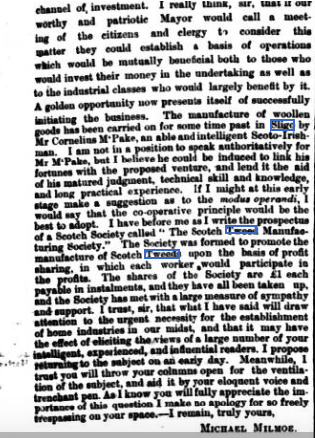

It was suggested by a merchant Michael Milmoe that a woollen industry be set up in the town as there was a lack of indigenous business. He suggested it be set up as a co-operative after the example of Scotch Tweed Manufacturing Society.

Letter to the Champion from Michael Milmoe in 1889, suggesting the opening of a Co-operative tweed manufacturing company.

In 1902 a co-operative shirt factory was set up in the Market Yard, a new building being purpose built for the task. Where this building was exactly is unknown. The Co-operative was a non profit business with shareholders created along the lines of the agricultural co-ops or the credit unions.

Several local gentlemen were early shareholders including Sir Josslyn Gore Booth of Lissadell, brother of Countess Markiewicz. The aim was to provide employment, training in skills and ultimately prevent emigration by building indigenous industry in Sligo.

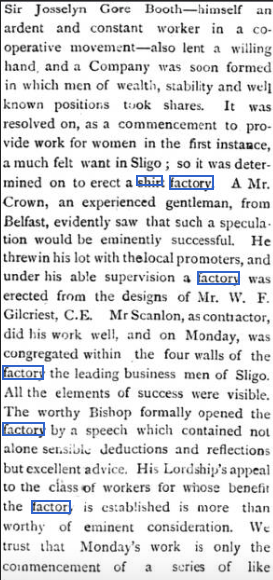

As the advertisement on the left shows by 1904 the Factory was producing finished products, including suits, boots, shirts and pants.

In 1907, the Factory, as it was called, was wound up as a co-operative as it was not making a profit. Bought out by Josslyn Gore Booth it became the Connacht Manufacturing Company. The company employed mainly women and appears by 1912 to have had a hundred employees.

This factory became involved in the 1913 Dock Strike in Sligo when it was closed either in sympathy with the strikers or it was shutdown by Sir Josslyn Gore Booth in an attempt to pressure the workers to come to a deal, its not clear exactly which.

Its not possible right now to tie down exactly which business was in which premises at the time of writing, but this is exactly why the records of buildings such as these are important, even those that now might not look like much, may have an important part to play in reconstructing our story of the past.

What is certain is that the history of Sligos early industrial enterprises is an important one. Firstly, any urban industrial history is unusual in Connacht and the west, which was almost totally rural at this time. Secondly, the founding of urban co-operative factories is a social history of great importance, especially as it is the socialist and syndicalist movements that lead to the unions, strikes and eventual revolution in Ireland at the start of the 20th century.

The Sligo Manufacturing Society s brief flourishing is part of understanding this social history, a history that continues to echo today with the continued importance of socialist politics in the town,

Events Leading to Demolition

September 2016 the building was recommended for inclusion in the RPS (Register of Protected Structures). a listing that seemed to ensure its destruction rather than preservation.

This author recommended retention of the building facade in a submission in 2016, and the further investigation of the rear building, which was flagged in the submission. The council executive at this point rejected facade only protection without a full architectural conservation report. But no mention was made of the second building.

At a council meeting that on 11th December 2017, Sligo County Council served a notice on those with responsibility for the property informing them that the building was considered to be a dangerous structure as per Section 1 of the Local Government (Sanitary Services) Act 1964

Two days later on the 13th December 2017, the Council received an engineer’s report in respect of the property which concurred with the Council in that the building was found to be “unsafe” and “structurally unsound”.

The report suggested that “repair is not an option” and recommends “early stage demolition” of the structure, also recommending that the building be made fully secure in order to prevent any unauthorised access.

On 10th May 2018 a conservation report was received recommending the “careful dismantling of the front facade” only and reconstructing it.” However, the headline on the same article contradicted this, declaring ” Report recommends knocking of facade of High Street building.” With one councillor claiming that “Demolition was the only plausible reality“. This despite the fact the report also contained a detailed strategy for the future reconstruction of the building’s facade.

It is unclear whether the author of the architectural heritage report ever gained access to the buildings, as they were declared unsafe before the heritage survey was done. Without access, the second building would not have been flagged and this would explain its absence from discussions.

It is also unclear whether the building was ever actually voted on to the RPS. If not, and if indeed it remained a candidate only for inclusion, it was in fact not protected, which left it open to clear the entire site and to ignore the recommendations in the heritage report and demolish the facade also, with no intention to reconstruct it.

The council issued proceedings and it was heard on the 4 September 2018. The buildings were demolished shortly after and the site cleared. There has been no further mentions of the site or reports or information on the history of the site.

There is a clear sequence here, that while it may be strictly legal, it is also clear that there is no real inclusion of heritage in the process. It highlights the missing integration of archaeological, historical and architectural information into the decision process. The final result is the loss of essential parts of Sligos unique history.

The Other Side of the Road

The events described above also leave it open to developers who may want sites cleared, as it is considerably cheaper to work from a cleared site than to have to retain and integrate historical features or facades,

It therefore becomes convenient to use the Sanitary Services Act as a loophole to get sites cleared completely, simply by neglecting buildings and allowing them to fall into disrepair. They can be destabilised by the removal of adjacent buildings and let become dangerous. The act is used to demolish the buildings, and this is sold to the public as a service.

Furthermore, the preservation order itself, because its not backed up ny the wherewithal of either money (to help owners and developers pay for works that are in the public interest) or technical expertise, is operating in reverse to its intentions. It is effectively comdemning buildings to be abandoned while the owners wait for them to become dangerous and then the demolition order can be activated.

As of June 2024, numbers 5, 6, 7 ,8, 9 High Street are now being demolished. And we worrtingly see precisely the same sequence of events. Calls from councillors to expedite the demolition. The declaration by the county executive of them being unsafe. There has been no mention of the retention of the street frontage, or of the building features , fittings or materials, if the recovery or re-use if features, or of architectural heritage surveys having been completed on the buildings.

None of these buildings are on the RPS and so are not protected. In fact, only three buildings on High Street are on the protected list. A quick look at other buildings on High street and Market street shows that even buildings with known historic features, such as wooden masts and timbers from 18th century sailing ships are not protected. A 17th or 18th century wall was located under no. 5 High Street, one of the buildings being demolished.

A possible late medieval wall was inspected c. 125m to the south at 5 High Street (Licence 02E1164, Bennett 2002:1664). The foundation trench of the wall was revealed beneath floor flags, its contents suggest a 17th/18th century date for the wall.

27 Market Street is on the NIAH architectural survey but not the council RPS.

Number 11,12 and 13 Market street all contain ships timbers from the 18th century as well as medieval pottery. For example,

A small sherd of possible medieval pottery was found towards the rear of the plot in disturbed ground. There were two purlins from a ship’s mast; Nos 12 and 13 are known to have similar timbers. Squared ship’s timbers, 1.18m by 0.25m by 0.15m and 1.5m by 0.25m by 0.15m, were found in the make-up of the back and front walls. The intact narrow wall between Nos 11 and 12, and presumably also between Nos 12 and 13, is of timber beam construction infilled with brick.

Conclusion : The Accountability and Oversight Deficit

Examining the role of oversight bodies or agencies responsible for heritage preservation, there seems to be no oversight or role within the council tasked with dealing with this important area.

Looking at the history of public interventions of councillors its clear theres a pattern, with repeated calls from the councillors to knock the buildings, facades and all, and with no mention of the heritage implications. They repeat the “urgency” and are disappointed when its not happening fast enough. While they no doubt have the best of intentions to provide facilities and amenitie for the public, the lack of joined up thinking on the historical issues risks undermining much of what makes Sligo unique, and ultimately destroying its prosperity in the process.

There are clearly serious gaps in the methodology used by the various arms of Sligo County Council and its Executive when it comes to implementing its own stated policy of either preserving the old town heritage or recovering it for museums, education and historical research purposes. If this is continued it will lead to the inevitable loss of more and more of the historical fabric, and with it the stories of past generations who lived and worked in the town.

The case illustrates the mechanism by which Sligo continues to lose heritage as it remains unrecognised. Heritage that has real monetary value that is being lost with the steady loss of unique heritage of the town

It is very important the various aspects of historical research, archaeology and development are balanced and integrated in the planning and development process. Currently, the heritage element is effectively missing, which results in the steady loss of both tangible and intangible history.

The council claims to support the idea of “heritage-led regeneration” and in the councils own words

“The character of historic town and village centres has been eroded in recent years, due in part to the following:

lack of awareness regarding the value of historic buildings, leading to demolition or neglect“

It further mentions that the policy to be adopted is to

“Require the retention and refurbishment of historic buildings in traditional town and village street-scapes. Demolition will be considered only in exceptional circumstances.“

There is no evidence in the cases mentioned above that the Council is capable of achieving these goals under its current operating procedures. In the councils own aims and objectives it says…

Sligo Section 2.05

The Planning and Development Act, 2000 (Part II, Section 10 and Part IV, Section 81) places an obligation on local authorities to include an objective for the preservation of the character of architectural conservation areas (ACA). The same Planning and Development Act places an obligation on all local authorities to include in its development plan objectives for the protection of structures, or parts of structures, which are of special architectural, historic, archaeological, artistic, cultural, scientific, social or technical interest.

These buildings and structures are to be compiled on a register known as the Record of Protected Structures (RPS)

Generally, encourage the re-use of older buildings through renovation.

Issues that can be addressed

Loss of Independent Urban Government

Loss of the Sligo Borough Council in 2013 has resulted in the loss of self government for the urban area of Sligo. A 400 year old borough vanished overnight, with a loss of institutional knowledge and an urban focus with different priorities and concerns to the large rural hinterlands of the west of Ireland.

Weakness of Irish Local Government

The weakness of Irish local government has a large part to play. Compared to Denmark, a similar sized European country, where 61 % of spending is through local government, in Ireland its 3%. Or put the other way arounf 97% of all money spent in the Irish state is spent by central government, an astonishing centralisation of decision making. The lack of discretionary spending power by the council greatly limits the effectiveness of interventions.

Ireland is the most centralised government system in Europe. This affects all areas of life in the regions, and it affects local authorities ability to implement there own heritage policies in a detrimental way.

Missing Public Archaeological Services

The lack of a dedicated archaeological and heritage arm of the council is hindering the integration of knowledge into the planning process. This has costs, both in lost opportunities to enhance the quality and tourist potential of heritage and in costs by outsourcing to expensive private consultants, most of whom are based a long way from Sligo.

Over-reliance on private contractors

The use of commercial contractors only in the provision of surveys and reports does not serve the public interest, but rather the interest of those paying for the service, in most cases the developer.

Lack of Museum facilities

The lack of a museum is a huge and ongoing issue in the loss of moveable artefacts in the county. Without a repository and conservation facilities there is a continual draining of historical artefacts and consequently the knowledge surrounding them to Dublin.

Failure of academic integration.

The loss of the archaeological department in the ATU has consequences on the ability to guide research into the different areas of Sligos history. Norman Sligo, Gaelic era Sligo, the imperial age, and the industrial and port history of the town are all avenues that are not the focus of coherent research programmes.

Even Yeats, the one historical figure remembered it seems, is often looked at in a sort of splendid isolation, as if the background that produced him and and his family was not important. As long as this narrow vision continues, Sligo will continue to lose more and more of its history.

References and Links

https://consult.sligococo.ie/sites/default/files/uploads/consultation/883/Draft%20Sligo%20CDP%202024-2030%20-%20Volume%202%20-%20October%202023.pdf

https://www.buildingconservation.com/articles/rooflighting/rooflighting.htm

https://www.independent.ie/regionals/sligo/news/report-recommends-knocking-of-the-facade-of-high-street-building/37097402.html

https://www.independent.ie/regionals/sligo/news/work-on-high-st-to-begin-shortly/37022440.html

https://www.independent.ie/regionals/sligo/news/legal-action-underway-in-a-bid-to-demolish-derelict-buildings-in-the-centre-of-sligo/a2129981890.html

https://www.independent.ie/regionals/sligo/news/report-recommends-knocking-of-the-facade-of-high-street-building/37097402.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1913_Sligo_Dock_strike

https://www.sligococo.ie/cdp/DraftCDP2017-2023ProposedChangesRPS.pdf

https://www.facebook.com/watch/?v=1135557606595784

https://consult.sligococo.ie/ga/consultation/housing-development-rathellen-finisklin-sligo-planning-application-bord-pleanala

Shed at Ettrick Mills, Canmore Scotland

https://canmore.org.uk/event/910734

https://www.nls.uk/learning-zone/politics-and-society/labour-history/fenwick-weavers/

Addendum :