Contents

“I know that there are many historians, or at least writers on historical subjects, who still think it necessary to apply moral judgments to history, and who distribute their praise or blame with the solemn complacency of a successful schoolmaster. This, however, is a foolish habit, and merely shows that the moral instinct can be brought to such a pitch of perfection that it will make its appearance wherever it is not required.

Oscar Wilde. 1889

Nobody with the true historical sense ever dreams of blaming Nero, or scolding Tiberius, or censuring Caesar Borgia. These personages have become like the puppets of a play. They may fill us with terror, or horror, or wonder, but they do not harm us. They are not in immediate relation to us. We have nothing to fear from them. They have passed into the sphere of art and science, and neither art nor science knows anything of moral approval or disapproval.”

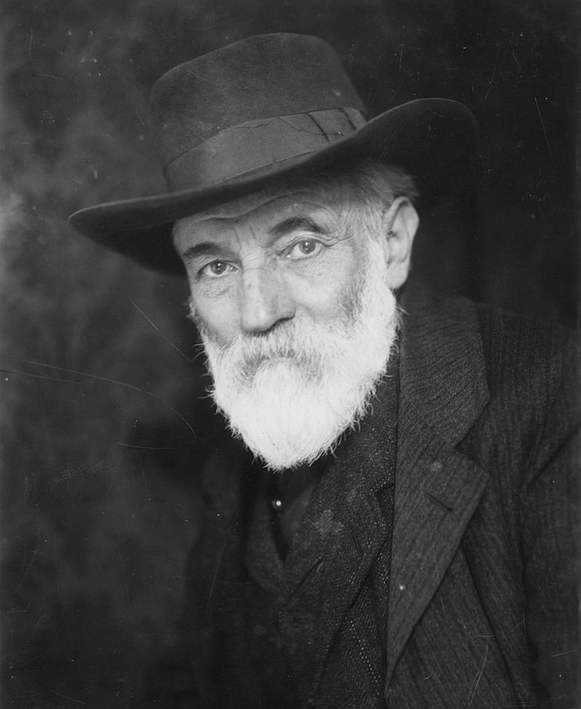

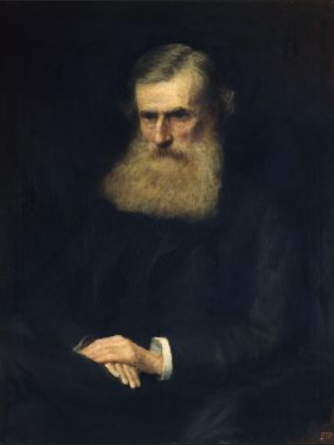

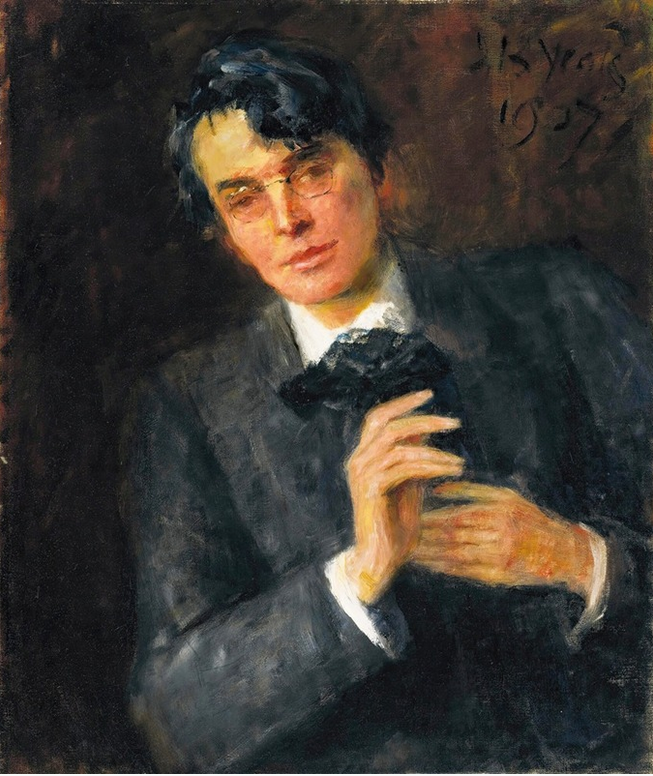

In 1914, a 75-year-old Irish artist living in New York wrote a letter that revealed the radical politics behind Ireland’s cultural revolution. John Butler Yeats—father of poet W.B. Yeats—described himself as a ‘radical socialist anarchist Home Ruler.’ This wasn’t empty rhetoric. It was the key to understanding how ancient Irish traditions merged with European revolutionary ideas to create modern Ireland.

This essay argues that John’s influence went far beyond his famous family. He helped create the intellectual foundation for a different kind of Irish independence—one rooted not in narrow nationalism or religious sectarianism, but in radical democracy, artistic freedom, and human dignity.

Most people know John Butler Yeats, if at all, as the father of poet W.B. Yeats. But this misses his central role in shaping the ideas that transformed Ireland from a colonial backwater into a modern nation. His unique achievement was fusing ancient Irish traditions of community and resistance with the most progressive European ideas of his time.

‘Had we married and lived together, our mutual unlikeness would have made us perfectly interesting to each other. I fancy you love Religion while I hate it, because of all its sins and wickedness. I am a radical socialist anarchist Home Ruler, everything you abhor, so I sometimes think it would be best to let this correspondence drop. If I go home this year we shall meet and have many talks and then start again to write to each other.’

John Butler Yeats, New York, 1914

There are many books and biographies written about the Yeats family, but few explore the philosophical atmosphere that John Butler Yeats cultivated around them—an atmosphere shaped not only by his idiosyncratic worldview but by the broader historical forces of 19th-century Ireland and Europe. His intellectual influence was profound, and understanding it requires looking beyond literary achievement to the radical cultural and political milieu he helped foster.

In this private letter, Yeats described himself as a “radical, socialist, anarchist Home Ruler.” Is this true? and if so what did John mean by this and what does it mean for our understanding of the Yeats family and their part in the lead-up to Irish independence. Johns self-description is consistent with the worldview he both lived and communicated to his children. As we shall see, there is ample reason to take his claim seriously.

To understand how remarkable this self-description was—and why it mattered for Ireland’s future—we must first grasp the world that shaped John Butler Yeats.

Ireland in 1839

When John Butler Yeats was born in 1839, Ireland was a country in the midst of profound transformation. With over eight million inhabitants, it was one of Europe’s most densely populated regions. The majority of these people—perhaps six million—spoke Irish as their first language, particularly in the western counties like Sligo where John’s family had deep roots. This was still a fundamentally Gaelic society, despite centuries of English rule.

But Ireland was also a country divided by religion, class, and competing visions of its future. Four distinct communities shared the island, each with different relationships to power and land—though historians typically describe only three, obscuring a crucial cultural divide within Catholic Ireland itself.

The Protestant Ascendancy—descendants of English and Scottish settlers—made up only about 10% of the population but owned most of the land. Within this minority, the Church of Ireland (the Irish branch of the Anglican Church) held the dominant position. As the official “established church,” it received state support and controlled much of the country’s wealth and political power, despite serving only a small fraction of the population. John Butler Yeats was born into this privileged but isolated world.

The Presbyterian community, concentrated in Ulster and descended from Scottish settlers, occupied a middle position. They had suffered some of the same restrictions as Catholics under the old Penal Laws, but generally enjoyed more economic freedom and social status.

Catholic Ireland, however, was deeply split between two very different worlds. Anglicised Catholics—descendants of the Old English who had settled in towns, along with others who had adopted English culture—dominated the emerging Catholic middle class. They controlled the established Catholic Church hierarchy, much of the middle level of administration, and the police force. English-speaking and culturally assimilated, they had learned to work within the colonial system.

But the majority of Catholics belonged to a very different tradition: the Gaelic Irish—millions of Irish-speaking tenant farmers, laborers, and Travellers (at this time known simply as the itinerant section of the Gaelic population) who remained culturally alienated from the state and its institutions. Concentrated especially in the west, they preserved not only the Irish language but ancient social structures, oral traditions, and a form of Catholicism quite different from the institutional religion of the towns. Their spiritual practices, rooted in centuries of clan-based community life, often resembled older pagan beliefs more than the standardized Catholicism preached from Dublin pulpits.

For centuries, the anglicised Catholic middle class had looked down on their Gaelic-speaking co-religionists as backward and primitive, viewing their cultural practices—and even their form of Catholic belief—as embarrassingly uncivilized. This internal division within Catholic Ireland would prove crucial to understanding the political and cultural struggles that lay ahead.

These religious divisions weren’t merely about theology—they reflected fundamental disagreements about Ireland’s relationship with Britain, who should control land and power, and what kind of society Ireland should become. The Church of Ireland community generally supported the Union with Britain (established in 1801) and viewed themselves as upholding English civilization against Catholic “barbarism.” Catholics increasingly sought self-government and an end to landlord dominance. Many Presbyterians, particularly in Ulster, had their own complex relationship with both British authority and Catholic nationalism.

This was the fractured world that shaped John Butler Yeats’s early life—a society where your religion determined not just your spiritual beliefs, but your political loyalties, economic opportunities, and social position. His later evolution from conventional Church of Ireland rector’s son to “radical socialist anarchist Home Ruler” represented a journey across these deep communal divides, toward a vision of Ireland that transcended sectarian boundaries entirely.

The young John Butler Yeats would witness this world’s dramatic transformation. The catastrophic Famine of the 1840s would devastate the Irish-speaking population, Catholic Emancipation would reshape politics, and new movements would emerge seeking to bridge Ireland’s divisions through shared culture and democratic ideals. His own intellectual journey—from religious orthodoxy to secular radicalism, from legal conservatism to artistic rebellion—mirrored his country’s struggle to imagine a different future.

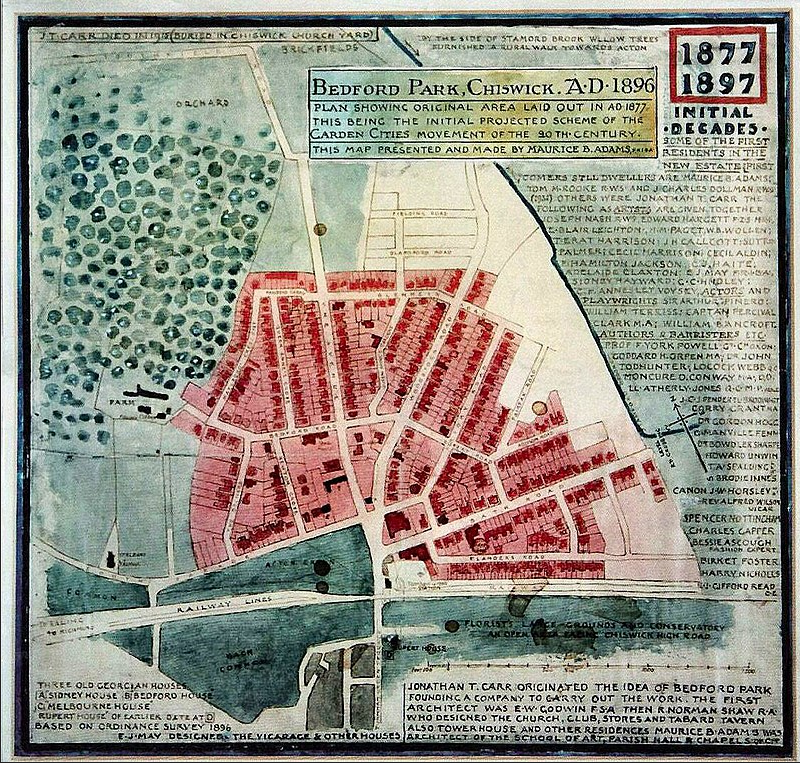

John Butler Yeats was instrumental in shaping what would become perhaps the most artistically ambitious family of Ireland’s so called “Gaelic Literary Revival”. George Bernard Shaw famously quipped that the movement had been “born in Bedford Park,“ the bohemian London suburb to which Yeats moved the family in the late 1880s.

Yet the “Gaelic Revival” was far more than a literary movement; it was a broad cultural project rooted in radical philosophy, history, and a desire for national renewal. At its heart were the most progressive intellectual currents of the 19th century—ideas that John Butler Yeats not only espoused but embodied.

This essay argues that Johns radicalism was not isolated but emerged from the fusing of two powerful currents: the ancient egalitarian ethos of Gaelic Ireland, particularly the west, and specifically Sligo in Johns case) and the libertarian-utopian socialism circulating among European intellectuals in the 19th century. The West of Ireland, in particular, preserved a form of communal, folk Catholicism, anti-clericalism, and collective social memory that contrasted sharply with the more institutional, empire-aligned Catholicism of the East of the country. These indigenous traditions, shaped by centuries of resistance and oral culture, provided fertile ground for the reception of continental radicalism.

Yeats’s later friendships with figures such as the Fenian leader John O’Leary and Russian anarchists like Stepniak and Kropotkin demonstrate that his politics were not merely affectations. Though not a militant, he stood intellectually not just close, but at the centre of revolutionary movements. Art and education, in his view, were not neutral disciplines but expressions of freedom and conscience—capable of reshaping the world as radically as any political act.

Similarly, his politics were shaped less by rigid ideology than by moral conviction. Influenced by John Stuart Mill, Yeats’s socialism was rooted in individual liberty, and disdain for the smug moralism of Victorian capitalism. Anarchy, at this time, and presumably to him, meant freedom from institutional authority—not lawlessness, but self-governance. Utopia was not a literal destination but a necessary ideal: a yardstick with which to measure the poverty of the present.

To contextualise his worldview, we must understand socialism and anarchism as they were understood in his time. Decades before the rise of Soviet-style Marxist authoritarianism, socialism was libertarian in character—decentralised, democratic, voluntary, and rooted in mutual aid. Anarchism, the most refined argument against traditional authority and the state, laid out a principled rejection of unjust hierarchy. It envisioned a society where freedom, cooperation, and art could flourish.

These ideas circulated widely in the radical cultural circles of London and Paris and other cities, where artists, poets, and political thinkers often mingled. In an era marked by vast inequality, industrial squalor, and disenfranchisement (even amongst men very few had the right to vote, and women not at all), millions supported these ideals as the promise of a fairer world.

Key figures like William Morris—artist, poet, manufacturer and socialist—who befriended Yeats in Dublin. Morris became a lasting intellectual influence, introducing William to the London avant-garde and helping shape the ethos of the Yeats household.

In Bedford Park, the progressive London suburb where Yeats settled in the late 1880s,he was surrounded by figures who personified the utopian and anarchist ideals of the age. For Yeats, these ideas were not abstract: they were to be lived, discussed, drawn, and written about.

John was famously talkative, and as his son William recounted in The Trembling of the Veil in 1915…

‘he spoke with sound good sense and delightful humour about art and poetry and people, and the influence that radiated out from him touched a whole generation.

But the utopian moment was not to last. The Bolshevik triumph in Russia of 1917 shifted the leftward imagination from decentralised, libertarian socialism to centralised, statist Marxism, polarising politics in general between left and the rising fascism of the right. . The earlier, more imaginative versions of socialism—particularly anarchist and utopian strains—were gradually eclipsed. Later generations would struggle to recall how dominant these traditions had once been among cultural and intellectual elites.

And yet it was precisely in this former world that the Yeats family came of age. The period in which John Yeats lived and his children grew up—referred to as La Belle Époque—was marked by astonishing technological and artistic progress, but also by crushing inequality and imperial expansion. The contradictions of this era shaped Yeats’s generation and gave rise to the radical philosophies he embraced. The words used then—socialism, anarchism, utopia—often meant something quite different from their modern associations. This drift in meaning risks obscuring the world Yeats inhabited and the ideals he embraced.

To understand the intellectual and cultural legacy of the Yeats family, and their impact on later Irish history, we must begin with this atmosphere of radical possibility—a worldview at once grounded in Ireland’s Gaelic past and connected to the most hopeful international visions of the 19th century, the intertwined threads of anarchism and republicanism.

John Butler Yeats stood rebelliously at the crossroads of both.

PART I: THE MAKING OF A RADICAL

“This above all: to thine own self be true“

Hamlet – Act 1 Scene 3 Polonius

John Butler Yeats was born on 16 March 1839 in County Down, the son of a Church of Ireland rector. His family lineage was clerical—his grandfather had been rector of Drumcliff in County Sligo, on the site of a 6th-century monastery founded by Columcille. His father grew up in this part of north Sligo, then on the estate of the Gore-Booth family, from whom Constance Markiwicz was to emerge. His father was kindly and easy-going, saying “if a man spoke harshly to you it was always your own fault” He provided ample paper for Johns drawing practice as a child, never complaining despite its cost.

While his father later moved to the parish in County Down where John grew up, John had numerous aunts and uncles around Sligo. That sacred landscape around Drumcliff would later become symbolically fused with his poet sons name: it was in the shadow of Ben Bulben at Drumcliff that William would choose to be buried.

Despite his religious upbringing, John grew up in a household that encouraged free conversation and critical thinking. His grandfather was remembered in Sligo for his lack of bigotry and respect for the Catholic majority in his parish—an unusual and admirable trait in an Anglican clergyman of the period. That spirit of tolerance and openness filtered down to the young John.

His early schooling at Atholl Academy on the Isle of Man was a brutal affair, presided over by a tyrannical Scottish headmaster. There, alongside Charles and George Pollexfen, John developed a lifelong hatred of compulsion in education and a deep interest in more progressive, child-centred methods of learning. These convictions would reappear throughout his life in his disdain for rote instruction and his championing of imagination and freedom in education.

Trinity and the Law: First Rebellions

He entered Trinity College Dublin in 1857, lodging with his grandmother, great-aunts, and Uncle Robert Corbet at Sandymount Castle. He described his grandmother and aunt as excellent conversationalists, and he regretted not having asked about the 1798 rebellion that they had lived through, describing them as “saturated through and through with the spirit of the eighteenth century”.

He studied under the progressive economist and poet John Kells Ingram—himself “well to the left” of most of his peers—John disliked Trinity intensely, viewing it as a colonial institution complicit in the oppression of Ireland. His thinking had already begun to move along radical, anti-authoritarian lines, though he remained, at least at this stage orthodox religiously.

His philosophy of life, even at this young age, was strikingly integrative—capable of holding in tension threads that others might see as contradictory: a passion for art and a hunger for justice, loyalty to Irish soil and immersion in European ideas, idealism and scepticism in equal measure. One contemporary remarked that he had “an extremely well-rounded philosophy of life“.

At the age of 23 he visited the Pollexfens in Sligo and became engaged to Susan Mary Pollexfen on 2 September 1862. Following his father’s death and his inheritance of the small Kildare estate, the couple married on 10 September 1863 at St. John’s Church, Sligo.

He studied law at King’s Inns in Dublin, entered the Irish Bar in 1866, and devilled (period of training under a senior barrister) for Isaac Butt, the Home Rule advocate. It was under Butt’s mentorship that John developed further his political sympathies for Irish self-government, though his legal career was short-lived—cut off in part by the revelation that he had been sketching a Queen’s Counsel “a little too effectively” in court. His cartoons were popular and funny it seems.

It was in this period that he gave one of his most revealing public addresses—The True Purpose of a Debating Society—delivered as Auditor of the Law Student’s Debating Society on 21 November 1865.

Rejecting outright the professional dogma that the role of a lawyer is to argue a client’s position, Yeats boldly declared that the Society’s aim must be nothing less than the pursuit of truth itself “truth for its own sake”. . A “restless craving for truth,” he argued, would eventually lead its members to “to desert their mimic debates and devote their faculties and energies, in real debate, to the attainment and promotion of truth”. Telling lawyers that their central concern must be only the truth is radical indeed!

This insistence on the centrality of truth—often inconvenient, sometimes impractical—would remain a defining characteristic of John Butler Yeats’s long life. He left the profession over this issue with the tension between the truth and working for a clients interests. From his refusal to practice law, to his uncompromising artistic ideals, to his late-life camaraderie with the realist painters of New York’s Ashcan School, he never strayed far from this early moral centre.

“Poetry and the imaginative life,” he would later write, “can only flourish where truth is of supreme moment; an education which contents itself with half-knowledge and half-thought will inevitably produce a crowd of sentimentalists and false poets and rhetoricians..”

A closer look at his Philosophy

John Butler Yeats’s belief in truth was rooted in a complex philosophical synthesis, shaped by his deep reading of John Stuart Mill and the influence of the Pre-Raphaelites. From Mill, Yeats absorbed a refined version of Utilitarianism — not Bentham’s strict pleasure calculus, but Mill’s emphasis on higher pleasures, individual liberty, and the moral importance of self-cultivation. This strain of Utilitarianism, grounded in the humanism of Epicurean ethics, held that the good life was one of rational moderation and emotional well-being — ideals that resonated with Yeats’s broader worldview.

Yet Yeats was acutely aware of the dark side of Utilitarian thinking when applied without imagination. He saw how the principle of “the greatest happiness for the greatest number” could be twisted to justify the sacrifice of minorities, or to impose order through authoritarian designs — as in Jeremy Bentham’s Panopticon, a model of surveillance architecture implemented in Sligo’s 19th-century prison. Though rational and seemingly humane, the Panopticon revealed a cold, bureaucratic logic that reduced people to units of behaviour — a danger Yeats would come to resist in both education and art.

In contrast, the Romantic idealism of the Pre-Raphaelites offered him a vision of human flourishing grounded in imagination, emotional truth, and aesthetic freedom. He admired their rejection of industrial uniformity and their return to sincerity, craft, and beauty. For Yeats, education was not the production of compliant citizens but the liberation of the soul. “False education,” he wrote, “is like the pressure which the Chinese mother applies to the feet of her infant… True education would liberate him so that he could sing in the open sky of knowledge and power and desire.”

“False education is like the pressure which the Chinese mother applies to the feet of her infant. True education liberates. The industrial movement would turn these peasants into smug artisans, without a thought that consoles or a hope that elevates… And yet man is naturally a singing bird… True education would liberate him so that he could sing in the open sky of knowledge and power and desire.”

Nevertheless John was aligned with the broader Pre-Socratic tradition underlying the Enlightenment—scientific and atheistic, concerned with moderation, clarity, and emotional well-being whilst elevating pleasure and eschewing pain—was evident in his belief that education should liberate, not constrain. His rejection of coercive schooling, and his ideal of nurturing imaginative freedom, marked a resistance to the reduction of human beings in an industrial system.

He blended this rational and materialist cosmology with an Aesthetic philosophy of art, a position summed up in “Art, for Arts sake”. They rejected outright the idea that art needed to be educational or say something. This movement was an influential counter to Victorian moral ideas that art was only good if it was educational or useful in some “improving” way. With roots in the German Romanticism of the late 18th and early 19th century, it was a key part of the Pre-Raphaelite school of painters that John was to fall in with during his first stay in London.

Yeats, like many in his time grappled with the seeming contradictions, elevating feeling and spontaneity above cool rational calculation. But, the common thread perhaps to the philosophical position that John built is that it was forward thinking, progressive, imaginitive and, remarkably, effective.

In this he resembled Oscar Wilde, another self described anarchist, aesthete and Irish revolutionary. Both Yeats and Wilde advanced a theory of aesthetics that viewed art not as a means to a mundane end (moral improvement, commercial gain, or social utility) but as an end in itself. They shared a deep conviction that emotion, beauty, and imagination were essential truths—not mere ornament.

Oscar was to have a profound effect on his son William who stayed with him over the Christmas of 1888. His advice to William on the importance of image had no small part in his success in later years.

Yeats’s notion of education as “a stirring up of the emotions” aligns with Wilde’s idea that feeling is more trustworthy than reason, and that truth reveals itself through aesthetic experience. For both, art was the supreme mode of ethical and philosophical inquiry.

Wilde, in The Soul of Man under Socialism, wrote that “the new individualism is the new Hellenism,” calling for a society that nurtures artistic and emotional freedom. Yeats’s idea that the fully emotional man achieves inner harmony echoes this—an artistic-ethical ideal of integrated selfhood, liberated from both economic constraint and ideological rigidity.

Both saw aesthetic feeling as the path to a deeper truth—neither hedonistic nor ascetic, but formative of character. Johns writings on portrait painting show this attitude in his desire to paint the essence of a person and not to be concerned only with the technicalities .

Interestingly the families had known each other a long time, and both shared an interest in Irish history and beleived in thefull development of Irelands cultural and political independence.

“Slowly I have come to feel,” he once reflected, “that affection for human nature which is at the root of all poetry and art, whether the poet be pessimist or optimist.” This affection, rather than a rigid ideology, appears to have been his compass in navigating politics, aesthetics, and personal life alike.

Letters to W. B. Yeats: ‘Now a most powerful and complex part of the personality is affection and affection springs straight out of the memory. For that reason what is new whether in the world of ideas or of fact cannot be subject for poetry, tho’ you can be as rhetorical about it as you please – rhetoric expresses other people’s feelings, poetry one’s own.’

His philosophy mixed Enlightenment scientific materialism. with a sophisticated philosophy of the importance of subjective experience and elevated truth and love to the highest place instead of god and saw change as the universal constant. this allowed him to integrate evolutionary theory with a philosophy of perception that was to become extremely important in the work of his children, but especially William.

‘I have no belief in what is called a personal God, but do believe in a shaping providence – and that this providence is what maybe called goodness or love, and that death is only a change in a world where change is the law of existence’ (Quoted in McGahern, op. cit., 1992.)

PART II: IRELAND IN CRISIS

Not So Revolutionary Ireland

The ideals John Yeats held—of truth, liberty, and human dignity—would eventually shape his views on Ireland and influence the course of his family’s life. He lived through a century of upheaval: from the collapse of the Gaelic world with the catastrophe of the Great Famine (1847–1850), through the Land War, the long struggle for Irish independence from the British Empire.

When John was born in 1839, Ireland was a very different place to what it was whern he died. In a country of at least 8 million people, the majority spoke Irish as a first language.

The Gaelic social order, based on clan structures, communal landholding, and a rich oral culture, had withstood centuries of colonisation. Its structures and values persisted, particularly in the West of Ireland, well into the 19th century. Despite official efforts to eradicate the Irish language and dismantle traditional modes of life, these communities retained a coherent worldview rooted in mutual obligation, spiritual continuity, and an ethic of collective dignity.

The Famine marked a final rupture. With mass death, eviction, and emigration, the last vestiges of autonomous Gaelic life were shattered. What survived did so in fragments—song, memory, folk practice—but the social and economic base was irreparably broken.

Born only a decade after Catholicism had been legalised, Yeats entered a society already transforming. Catholic Emancipation had been secured in 1829 through a mass campaign led by Daniel O’Connell, which brought Catholics into civic life and redefined the Irish political landscape. But the Ascendancy, still clinging to power and privilege, regarded this shift with deep suspicion. The Catholic Church, newly empowered and increasingly aligned with British administration, quickly established itself as a dominant force in Irish public life. Its influence reached far beyond the sacristy—shaping education, gender roles, social morality, and national politics.

O’Connell had demonstrated the power of mass democratic mobilisation—but at a cost. To build a broad national movement, he stitched together the Irish-speaking west and the English-speaking east under the banner of Catholic nationalism. This alliance brought momentum, but also contradiction. The interests of rural Irish-speaking peasants diverged sharply from those of urban Catholics and the Old English gentry. In practice, many were excluded: Gaelic speakers, Protestant liberals, and secular republicans found themselves pushed to the margins.

Though O’Connell spoke Irish, he dismissed its role in the modern world. “The superior utility of the English tongue,” he claimed, outweighed any sentiment over the “gradual abandonment” of Irish. His vision was parliamentary, moderate, and loyalist: an Irish parliament under the Crown, within the Empire, and morally governed by the Catholic hierarchy. He had little sympathy for revolution. Catholic rights, once achieved, chiefly benefitted the Catholic middle class and aristocracy—leaving the Gaelic poor as impoverished as ever.

During the 1830s, O’Connell turned his attention to repealing the Act of Union, which had abolished the Irish Parliament in 1801 and imposed direct rule from Westminster. But neither the Protestant Ascendancy nor the Catholic middle class embraced the prospect of an Irish parliament, each fearing domination by the other.

These same blocs, decades later, would advocate for partition to protect their sectarian interests—revealing how shallow their commitment was to representative democracy.

This was the fractured political landscape inherited by Thomas Davis and the Young Ireland movement, which sought to imagine a very different kind of Ireland—non-sectarian, historically grounded, and radically democratic.

Thomas Davis (1814–1845) was a foundational figure in Irish nationalism and cultural revival, whose short life left a lasting impact. A Protestant and a romantic idealist, he was a leading voice in the Young Ireland movement and co-founder of The Nation newspaper.

Davis championed the idea of an inclusive Irish identity rooted in shared history, culture, and language rather than sectarian lines. He saw poetry, music, and historical memory as essential tools for nation-building, believing that Ireland’s future independence depended on reclaiming its past. Through his writings, Davis fused political activism with cultural renaissance, laying the intellectual groundwork for later movements that sought not only freedom from empire but a renewal of Irish civilisation itself.

Young Ireland’s Alternative Vision

Initially, the men, including Davis, who were to become the Young Irelanders were supportive of O’Connell’s movement, but the cracks in this coalition began to show as early as the 1840s. One major flashpoint was the proposed Irish University Act of 1845, which aimed to provide secular, mixed-faith higher education. O’Connell opposed it; his more radical allies supported it.

These rebels, whom he derisively dubbed “Young Irelanders,” broke with him entirely. They began publishing The Nation in 1842, championing a republican and secular nationalism that echoed the ideals of Wolfe Tone and the United Irishmen. Their vision was of a non-sectarian Ireland, where Catholic and Protestant alike could unite under the banner of liberty and equality. Thomas Davis excoriated O’Connells pious bigoted Catholicism in The Nation, warning where it would inevitably lead:

‘The objections to separate education are immense; the reasons for it are reasons for separate life, for mutual animosity, for penal laws, for religious wars. ‘tis said that communication between the students of different creeds will taint their faith and endanger their souls.

They who say so should prohibit the students from associating out of the college even more than in them … let them prohibit Catholic and Protestant boys from playing, talking, or walking together … let them establish a theological police – let them rail off each sect … into a separate quarter; or rather, to save preliminaries, let each of them proclaim war in the name of his creed on the men of all other creeds, and fight till death, triumph, or disgust shall leave him leisure to revise his principles.’

Thomas Davis

But O’Connell vehemently opposed the bill, along with the Catholic hierarchy, calling the proposed colleges “godless.” and accusing Davis maliciously of wanting to declare it a “crime to be a Catholic”.

In the ensuing debate, Davis was reportedly reduced to tears. He knew what was at stake. O’Connell and the bishops feared losing control of education, and O’Connell claimed he was making a stand for “Old Ireland”—an ironic claim from a man willing to discard the Irish language and accommodate British rule. O”Connells decisions were to lead to centuries of strife in Ireland, but there had been another path.

Davis had laid out a radically different vision. He admired French historians that had emerged since the French Revolution, particularly Jules Michelet—the passionate romantic historian who portrayed the common people as the true heroes of France’s past. Michelet’s histories celebrated popular movements and democratic uprisings, showing how ordinary citizens had shaped their nation’s destiny.

But he most revered Augustin Thierry, whom Davis exalted above “any other historian that ever lived.“ Thierry was a former secretary to the utopian socialist Claude Henri de Saint-Simon who had revolutionized historical writing by focusing on social conflict rather than political chronology. His groundbreaking works—Letters on the History of France and History of the Conquest of England by the Normans—analyzed the past as a struggle between different peoples, classes, and social systems. Rather than celebrating kings and battles,

Thierry studied how medieval French communes had fought feudal lords for self-governance, creating islands of democratic freedom centuries before the modern age. For Thierry, history was not the story of great men imposing their will, but of ordinary communities organizing to defend their liberty and human dignity against oppressive hierarchies.

Saint-Simon envisioned future social harmony, while Thierry applied those ideals to the past—writing history as the clash of classes, cultures, and ideals. Thomas Davis now absorbed this framework and mapped it onto Ireland. Where others saw a contest of nations or religions, Davis saw the historical struggle of peoples and systems.

Saint-Simon, now regarded as a founder of utopian socialism, was a major influence on John Stuart Mill and on foundational anarchist thinkers such as Pierre-Joseph Proudhon.

His vision of non-authoritarian, cooperative society informed Thierry’s historiography, which Davis in turn adopted as the philosophical basis for Irish republicanism. In this way, the early libertarian threads of European anarchist and socialist thought entered directly into the Irish radical tradition, underpinning the intellectual foundation of the later republican movement.

Davis imagined a republic in which all creeds and classes would be equal. He railed against the inhumanity of laissez-faire capitalism and the devastation it had wrought on England’s industrial cities. In Dublin, Davis addressed Protestants directly, saying: “Gentlemen, you have a nation.”

Through The Nation, Davis promoted the Irish language, called for a national museum, advocated for the protection of antiquities, and protested the desecration of sacred sites like Newgrange. He fused romantic and heroic nationalism with secular republicanism and a deep respect for Gaelic culture. His programme laid the groundwork for a cultural revival intertwined with progressive political ideals.

The republican movement now picked up a cultural programme.

In the Nation he urged,

‘the language of a nation’s youth is the only easy and full speech for its manhood and for its age. And when the language of the cradle goes, itself craves a tomb. A people without a language is only half a nation. A nation should guard its language more than its territories – ‘tis a surer barrier and more important frontier than fortress and river“

Thomas Davis

His fusing of a romantic and heroic nationalism, secular republican principles as well as promotion of the Irish language and the Gaelic past of the country were to create a current counter to the socially conservative forces of both Protestant and Catholic Ireland. These, and not strict religious divides were to draw the real lines of battle for the next chapters of Irelands history.

Where O’Connell saw Ireland’s future as clerical, moderate, and tied to Britain, Davis saw it as secular, heroic, and rooted in the Gaelic past. He sought a cultural revival alongside political independence—a republic of reason, memory, and inclusion. He also insisted that any future Irish history must be free of sectarianism:

“The greatest vice in such a work would be bigotry—bigotry of race or creed. We know a descendant of a great Milesian family who supports the Union, because he thinks the descendants of the Anglo-Irish—his ancestors’ foes—would mainly rule Ireland, were she independent.

The opposite rage against the older races is still more usual. A religious bigot is altogether unfit, incurably unfit, for such a task; and the writer of such an Irish history must feel a love for all sects, a philosophical eye to the merits and demerits of all, and a solemn and haughty impartiality in speaking of all.”

Though Davis’s public life lasted only three years before his death from scarlet fever at age 30, his influence was immense. His funeral galvanised a generation, including Jane Wilde (Oscar Wilde’s mother), who became a leading voice of the 1848 rebellion under the pen name “Speranza.” Her husband, Sir William Wilde, began collecting Irish antiquities, laying the foundation for what would become the National Museum of Ireland.

The Third Way

Davis’s vision was excellent. practical and inclusive, but it was also perceived as a threat to the established powers rooted in sectarian, military, financial and landed power structures. Neither the Protestant Unionist elite, nor the conservative Catholic middle classes rooted in the anglicised, hierarchical world of the Pale would subscribe to something that threatened their position.

Davis had created a third way—a fusion of progressive, radical republicanism, and Enlightenment secularism. He brought together Enlightenment rationalism, Gaelic romanticism, and an inclusive civic nationalism that defined the broadest possible Irish identity.

Outside of the more educated and left leaning Protestants, nowhere was this vision more potent than in the Gaelic-speaking west—the majority population of Ireland in the 1840s. Here, Davis’s fusion of cultural revivalism and secular republicanism offered the hope of a radically inclusive Irish modernity, where their culture would achieve equality before the law for the first time in centuries…

The Empire Strikes Back

Before this awakening could take flight, disaster struck. Davis died suddenly of scarlet fever in September 1845, at just 31 years old, just as his vision of an inclusive, secular Irish republic was gaining momentum among both Gaelic Ireland and progressive Protestants.

His funeral became a defining moment for a generation of Irish intellectuals. Thousands followed his coffin through Dublin’s streets, including Jane Wilde—Oscar Wilde’s mother—who would become a leading voice of the 1848 rebellion under the pen name “Speranza.” The ceremony galvanized writers, artists, and revolutionaries who saw in Davis’s death the loss of Ireland’s democratic future. Many would spend the rest of their lives trying to fulfill the promise of his brief but transformative career.

That same year, the potato blight arrived—a fungal disease that destroyed the crop upon which millions of Irish people depended for survival. The potato had become the staple food of the Gaelic poor, particularly in the west, where tiny plots of land could barely sustain families even in good times.

What might have been a crisis became a catastrophe, exacerbated by the British government’s economic dogma and latent racial prejudice. The Great Hunger killed over a million and drove a million more to emigration within just a few years.

The catastrophe devastated the Gaelic-speaking west. Though Westminster bore ultimate responsibility, Dublin’s role was not innocent. At the height of starvation, new Vagrancy Acts were passed in 1847, making movement out of one’s home district illegal. While no famine existed in the more monetised east, mass displacement from the west was criminalised. For many, the only escape lay westward to the coffin ships.

The response of the authorities discredited not only the government but O’Connell and the Catholic hierarchy. The scale of the disaster radicalised survivors across Ireland and in the diaspora, especially in America. Among them, a lingering suspicion grew: that the famine was not merely a failure of policy, but a form of calculated clearance. The Gaelic poor were viewed by many in power as an impediment to prosperity—an expendable underclass in a colonial economy.

The famine wiped out the subsistence economy of the west. It freed land for exploitation by capital, integrating the west into the east’s monetised economy and completing a project of enclosure and clearance that had been attempted before but had been impossible to achieve.

The failure to intervene effectively in the Famine, many believed, was no accident—it aligned with the interests of landlords, administrators, and industrialists. It was not only London that benefited; Dublin and the east did too by the destruction of the population with whom Davis had hoped to carry through the programme of a new Ireland.

In other words, capitalist driven land clearance allied to entrenched middle class interests , both Protestant and Catholic drove much of the failure to intervene in any meaningful way to prevent the disaster. Certainly, the survivors who reached America thought so, and rapidly militant societies sprung up to hit back at the Empire.

“… The Celt, like the Red Man, melts away from the land which he has occupied and reclaimed for a long time anterior to the dawn of history. […] The rushing advance of western civilization drives the Indian from his forests and prairies… Something of the same character, but more cold-blooded and cruel, is operating on the fortunes of the Celtic race both in Ireland and Scotland.”

Freeman’s Journal (1851) 5 August

Ironically, the famine also hastened the decline of the old Protestant landlord class. Their estates, gutted of tenants, became unviable. The social system imposed since Cromwell began to collapse under its own weight.

But culturally, the Gaelic west no longer posed an immediate threat. It could now be romanticised safely—like the Native Americans after the Indian Wars—its rough edges shaved off, its spiritual and collective ethos appropriated.

A new nationalist identity was forged in Dublin, equated with middle class Catholicism. Anglicised Catholics who had historically defined themselves as English could now embrace Irishness on terms they controlled.

The progressive vision of Davis—secular, non-sectarian, rooted in historical consciousness—was pushed to the margins. Those who held to it were now painted as extremists. Irelands Catholic middle classes in conjunction with the rising power of the church, rebranded the national story, obscuring the differences between east and west, between collaborator and resister, and between survivor and beneficiary. The Gaelic world could be mourned, mythologised, even mined for heritage—but never fully acknowledged as a living challenge to the new order.

PART III: JOHN BUTLER YEATS AND THE RADICAL TRADITION

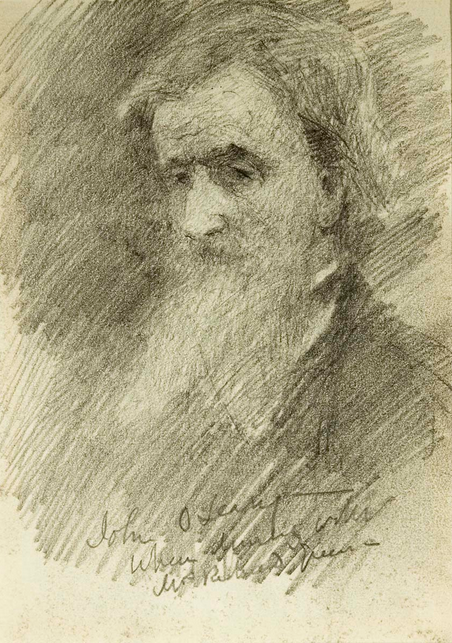

John O’Leary and the Revolutionary Legacy

In Tipperary in 1846 , a young John O’Leary was convalescing from illness as the Famine gathered pace around him. It was during this period that he discovered the writings of Thomas Davis—and was immediately converted. While studying law in Dublin, he joined the radical wing of the Young Irelanders, and when they launched a failed rebellion in 1848, he returned to Tipperary to join it.

The rising collapsed, as did another attempt in 1849. Disillusioned, he abandoned his legal career after discovering it required an oath of allegiance to the Crown. ibid (to this day the Kings Inns of Dublin and London are linked(

Like many other disillusioned republicans, O’Leary came to believe that Wolfe Tone’s approach—an oath-bound secret society—was the best model for revolution. In 1858, he was recruited by James Stephens to the newly formed Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB), a clandestine movement dedicated to armed insurrection. O’Leary later admitted rather amusingly, he was never entirely sure if it was originally called the Irish Republican Brotherhood, or the Irish Revolutionary Brotherhood; as before 1867, it was always simply referred to as “The Organisation.”

Driven underground, the radical avant-garde became the torchbearers of both Gaelic cultural memory and the republican tradition of the United Irishmen. O’Leary became editor of The Irish People and treasurer of the IRB. For this, he was arrested and sentenced to twenty years’ exile for treason.

In exile, mostly in Paris, O’Leary maintained his belief that Davis’s cultural programme was as vital as military action. He returned to Ireland in 1885, an elder statesman of the republican cause. Cautious but committed, he joined the Constitutional Club in Dublin and sought to avoid the strategic missteps of the past.

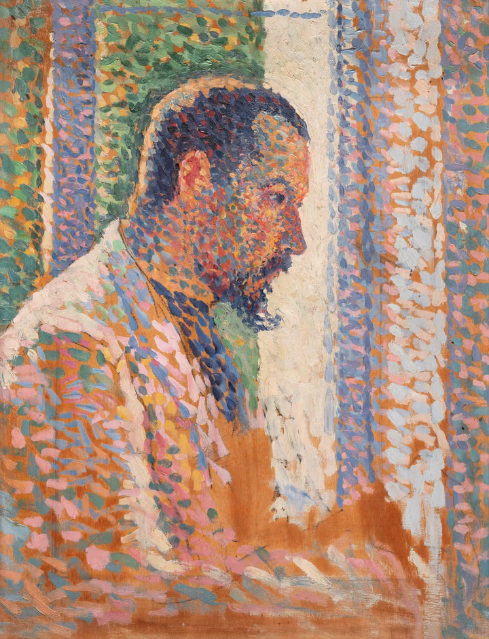

His impact on the Yeats family was immense. His friendship with John Butler Yeats would lead to a striking portrait—widely considered Yeats’s masterpiece—and left a lasting impression on the younger Yeats children. As John later wrote to O Leary:

: ‘…If you will allow me to say so, when I met you – your friends – I for the first time met people in Dublin who were not entirely absorbed in the temporal and eternal welfare of themselves … It was meeting you all that has left an impression on my young people that will never be quite lost.’

There is some evidence, mentioned in connection with the later president of the IRB council Bulmer Hobson, that John Butler Yeats during his time in London was a senior IRB contact for revolutionaries arriving in the city—possibly assisting with communications or introductions. His good friend John O Leary was the president of the IRB throughout this period from 1891 to 1907.

O’Leary’s role as mentor and bridge between generations is often understated, he remained the president of the IRB until 1907. During his tenure, the armed force element had atrophied its true, but the project that the generation who had witnessed the failure of half baked rebellions in the pasdt had been to create the conditions, socially and intellectually that would enable any such asttempt at rebellion successful.

This legacy would resonate deeply with John Butler Yeats and his circle, preparing the ground for his engagement with other radicals in the London avant-garde, including Stepniak, Morris, and Kropotkin.

Exiles in Garden City

In the late 1880s, John Butler Yeats made a decision that would shape his family’s future. He moved them to Bedford Park in London—a radical experiment disguised as a quiet suburb.

From Law to Art

This wasn’t John’s first time in London. Back in 1863, he had shocked his wife’s wealthy Sligo family by abandoning his legal career to become an artist. He enrolled at Heatherley’s Art School, where he met other young rebels who admired the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood—artists who mixed poetry with medieval romance and a love of nature.

In London, John discovered Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species. He borrowed it from his friend Samuel Butler, the writer who penned Erewhon and an early essay about machine intelligence called “Darwin Among the Machines.” For John, Darwin’s ideas meant more than just science. They freed him from religious dogma.

“I came to recognise natural law,” he later wrote, “and then lost all interest in a personal god, which seemed merely a myth of the frightened imagination.”

Family Struggles

The years that followed were difficult. The family moved constantly between Dublin, Sligo, and London. Money was tight. John’s marriage suffered. Sometimes the children had to stay with relatives in Sligo—an experience that deeply shaped their love of Irish culture.

Two children died young. But four survived: William (who would become the famous poet), Susan (nicknamed Lily), Elizabeth (called Lolly), and Jack.

The Garden Suburb Experiment

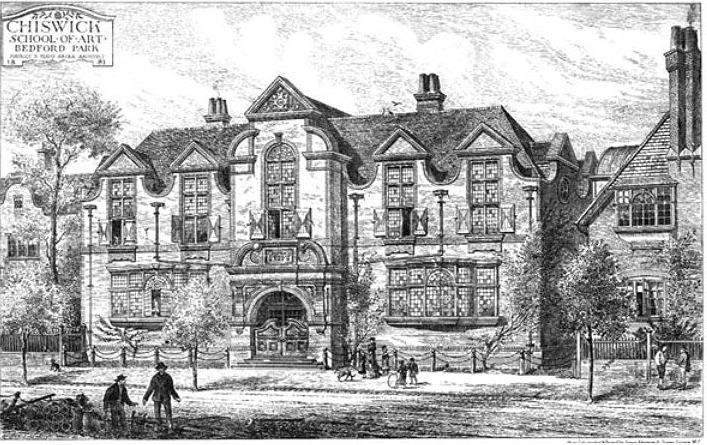

In 1887, the family finally settled at 3 Blenheim Road in Bedford Park, Chiswick. This was no ordinary suburb. Bedford Park was the world’s first purpose-built “garden suburb”—a revolutionary attempt to solve the problems of industrial city life.

Developer Jonathan Carr had created something new: a community that combined urban convenience with rural beauty. The suburb featured twenty houses with built-in artists’ studios as well as a community club and church that welcomed different faiths.

The underlying philosophy was radical for its time: that beautiful, well-designed environments could create better people and a better society.

Its tree-lined streets, Arts and Crafts architecture, and integration of green spaces with residential areas embodied a philosophical commitment to reconciling urban convenience with rural tranquility.

This “garden suburb” concept represented a middle path between the overcrowded industrial city and isolated country living, promoting the idea that thoughtfully designed communities could foster both individual flourishing and social harmony.

Bedford Park’s emphasis on aesthetic unity, community facilities like the club and church, and its appeal to artistic and intellectual residents demonstrated the movement’s underlying belief that physical environment profoundly shapes social and moral development—a conviction that would become central to progressive urban planning throughout the twentieth century.

Its red-brick houses and leafy lanes hid a community that embraced many of the values John held dear: environmental awareness, gender equality, world religions, and anti-imperialism. Twenty of the houses featured in-built studios for artists. Here, he lived from 1888 to 1902.

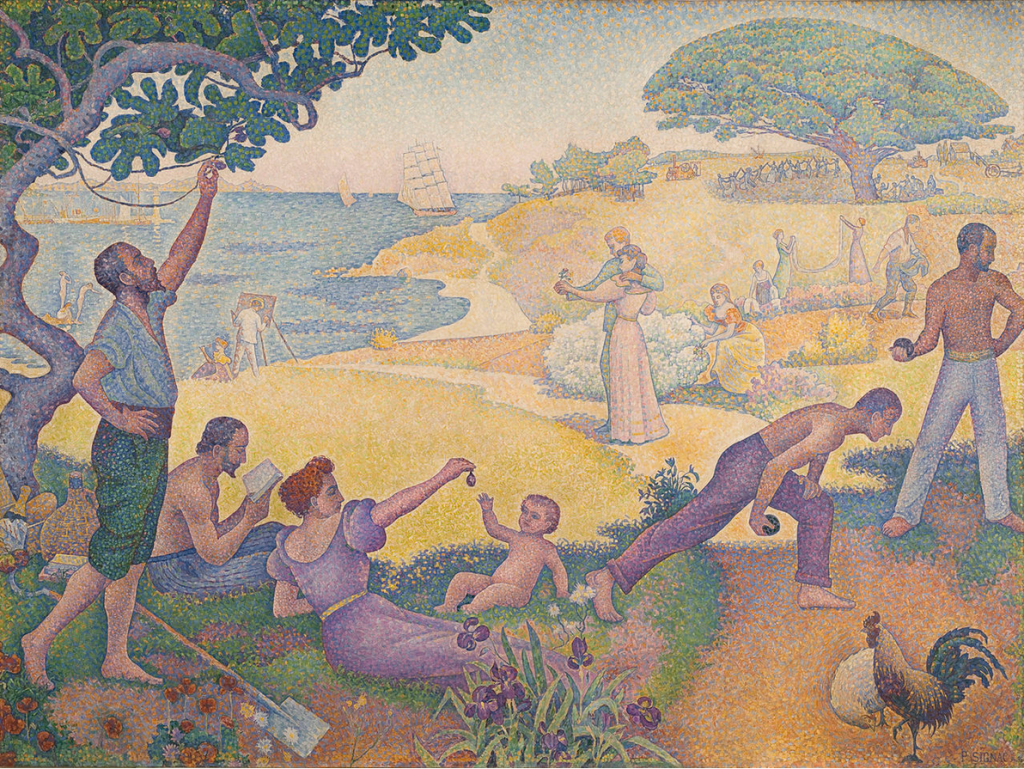

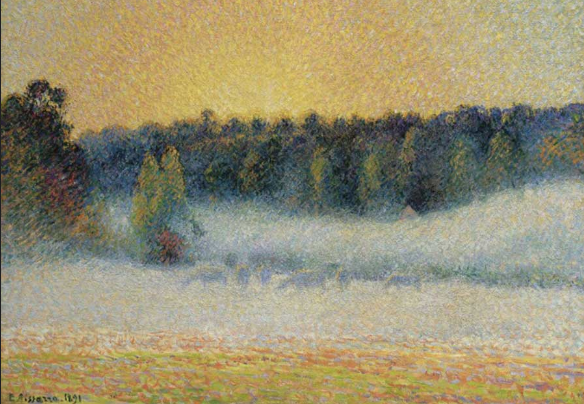

The French Impressionist Camille Pissarro captured its atmosphere in Bath Road, London (1897), a luminous depiction of the suburb’s tranquil modernity. Pissarro, whose son moved to Bedford Park, was himself a committed anarchist and a subscriber to Le Révolté. He corresponded with Jean Grave and counted Paul Signac and Henri-Edmond Cross among his comrades in aesthetic rebellion. Paintings like Meadow with Cows, Mist and Setting Sun at Eragny (1891), expressed a quiet radicalism—a belief in everyday beauty, peasant life, and communal values.

Pissarro was a committed anarchist who subscribed to the radical publication Le Révolté. He corresponded with leading anarchist thinkers and counted revolutionary artists Paul Signac and Henri-Edmond Cross as close friends. His paintings expressed what he called “quiet radicalism”—a belief in everyday beauty, the dignity of peasant life, and communal values.

As William Butler Yeats later wrote of his first experiences of Bedford Park::

“We were to see DeMorgan tiles, peacock-blue doors and the pomegranate pattern and the tulip pattern of Morris, and to discover that we had always hated doors painted with imitation grain, the roses of mid-Victoria, and tiles covered with geometrical patterns that seemed to have been shaken out of a muddy kaleidoscope. We went to live in a house like those we had seen in pictures and even met people dressed like people in the story-books.”

The political radicalism of Bedford Park was real. It was home to Russian exiles like Stepniak and Peter Kropotkin, who envisioned cooperative society and artistic freedom. At the same time, Morris’s Socialist League brought together artists, revolutionaries, and utopians under a banner of ethical socialism. John had taken William to hear Morris speak in Dublin, and even sketched him during his 1886 lecture The Aims of Art at the Contemporary Club.

Bedford Park was home to creative networks that embraced traditional crafts, environmentalism, healthy housing, egalitarianism, spiritual pluralism, and anti-colonialism. Its residents included artists, vegetarians, feminists, abolitionists, and anarchists. This was where John Butler Yeats encountered the intellectual milieu that would influence him and his children profoundly.

John Butler Yeats shared the Utopian dream that science and applied knowledge might one day free humanity from brutal toil. As he wrote in 1917, he looked to a millennium when “Science and Applied Science release us from the burthen of industry and necessity,” even while warning that without moral vision, such liberation might reduce people to mere brutes.”

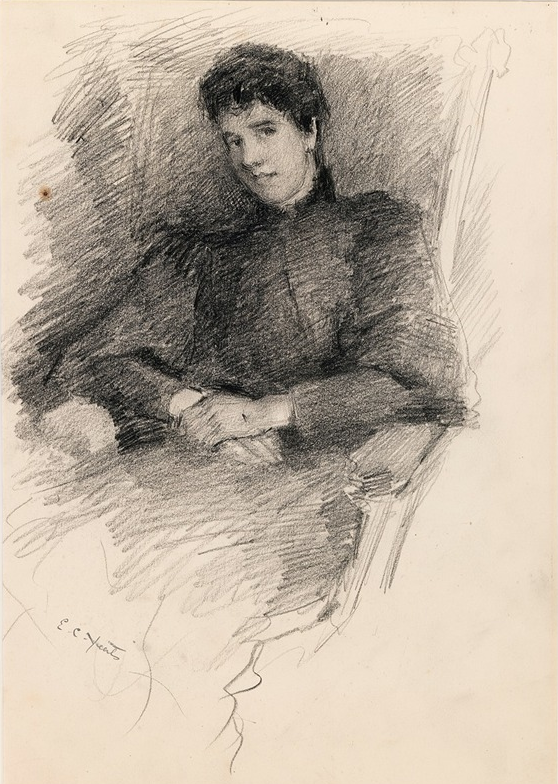

John’s daughters Susan and Elizabeth attended the Chiswick School of Art and later trained in embroidery and printing under May Morris, William Morris’s daughter. John’s son Jack absorbed the aesthetic vision of Walter Crane, the cartoonist of the Socialist League, while William made early connections with Oscar Wilde and other literary figures through their Bedford Park neighbors, including the printer Elkin Mathews.

Bedford Park was a crucible for a new way of life. As John put it, it was a place where “intellect and emotion shake hands in eternal friendship.” The utopian community of Bedford Park gave shape to a lifelong aspiration: that art, liberty, and radical ethics might form the foundation of a better society. It was in fact the origin of the modern small house and suburban blueprint of living which was to be replicated across the world in the 20th century.

Bedford Park wasn’t just John’s home from 1888 to 1902. It was a laboratory where he and his children could explore how art, politics, and daily life might be transformed. The ideas they encountered here—about beauty, community, and human dignity—would later inspire their efforts to create a new kind of Ireland.

The effect on Johns children was profound, as it provided both the education and the opportunities through contacts to express themselves—William, Lily, Lolly, and Jack—who would try to reimagine Ireland in the same spirit. Their next chapter would take up the promise of Bedford Park and attempt to plant its ideals in Irish soil.

The revolution, it turned out, could begin in suburbia.

The Arts And Crafts Movement

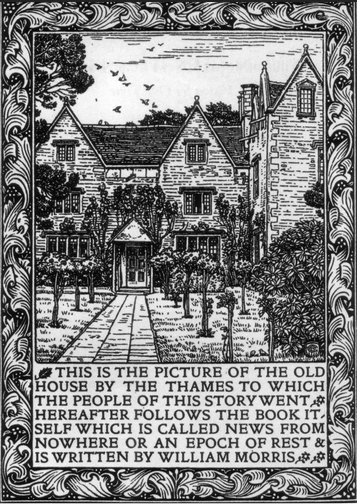

William Morris, president of the Socialist League brought together artists and revolutionaries. John sketched Morris during his 1886 lecture on utopian socialism at Dublin’s Contemporary Club—an event that made a powerful impression on young William Butler Yeats, who attended with his father. Morris’s News from Nowhere, a utopian novel envisioning a decentralized, craft-based society, became a blueprint for the Yeats household.

These strands fused in a practical way in the firm Morris Faulkner & co a interior decoration a furnishings and decorative arts manufacturer and retailer founded by the artist and designer William Morris the firm’s medieval-inspired aesthetic and respect for hand-craftsmanship and traditional textile arts had a profound influence on the decoration of churches and houses into the early 20th century.firm founded that became influential in mural decoration, furniture, metal and glass wares, cloth and paper wall-hangings, embroideries, jewellery, woven and knotted carpets, silk damasks, and tapestries.

Bedford Park was also home to a transatlantic artistic network that fed into the rising Arts and Crafts movement. Figures such as Edward William Godwin (he had designed some of the houses in Bedford Park)—deeply influenced by Japanese design—and his son, the theatrical innovator Edward Gordon Craig, helped shape a fusion of medieval, modern, and Asian aesthetics. Frederick York Powell, a historian, socialist, also a member of Stepniaks circle and an “Ardent champion of Irish learning’, John had hoped to have WB work with him, and lamented when William took up with Lady Gregory instead.

Years later in 1916 WB Yeats was to replicate the ambition of these visions wwith his purchase of the tower house at Coole Park and the engaging of an Arts and Crafts architect to design a new form of Gaelic inpired interiior decoration. Furniture and metalwork and textiles were all commissioned for this project, which Yeats perhaps intended to be as inspirational in Ireland as Morriss Red House had been in England.

William Morris workshops where Johns daughter Susan was to work in the embroidery section for several years were nearby.

Morris held here his meetings with a wide range of free thinkers and avant garde social reformers

Here Pyotr Kropotkin was a regular guest. quickly became part of Morris’s Sunday “Socialist League” gatherings, in the coach house to the left of the main house.

There he joined a political circle that included Bedford Park’s Ukrainian exile Sergius Stepniak,, Eleanor Marx, daughter of Karl, and two Irish socialists, the playwright George Bernard Shaw, and Annie Besant who would become the first woman President of the Indian National Congress. WB Yeats quickly joined the circle a;so.

Many of the same activists also attended Bedford Park Club debates, including those on Indian Independence and Irish Home Rule, as did occasional visitors such as Roger Casement and John O’Leary.

In one of his letters written from Bedford Park, he reports on a visit by the old Fenian, John O’Leary to the Calumets, a club in Bedford Park. John was disappointed that O’Leary had avoided ‘dangerous subjects’, and so he had tried to ‘roll in the apple of discord’, but to no avail.

A description of Morris philosophy at the time goes thus

All who knew him knew he was profoundly convinced that so long as private ownership in the means of life obtained a true material, intellectual, and moral human life for the mass of the people was impossible.

Yet he could not conceive William Morris sitting down satisfied with the mere alteration of material and physical conditions. He grasped that the main thing to be done was to give opportunities for character to grow.

It was the building up of character. The true worth and value of human life lay in the fact that every man, woman, and child was an improvable being; that there existed in the world certain artificial conditions that hindered, crushed, and degraded human life; that it was the duty of society to change those conditions, in order that the highest possibilities of human life might have free play and develop—that made Morris’s Socialism that of the true Social Democrat, and the Hammersmith Socialist Society would best perpetuate his memory by carrying on its work on those lines.

Herbert Burrows

Stepniak (Sergey Kravchinsky) and Peter Kropotkin, Russian anarchist exiles who joined the Bedford Park salon culture. Most notoriously, he had assassinated General Nikolai Mezentsov, chief of Russia’s secret police, with a dagger in St. Petersburg in 1878.

Stepniak—whose house backed on to the Yeats garden was a Russian revolutionary, writer, and theorist.

He was found dead in 1895 after being struck by a train at a level crossing. Officially deemed an accident, some suspected Russian secret police involvement. John Yeats had been at Stepniak’s home the night before.

The official version was that Stepniak was struck by a train at a level crossing in Bedford Park, London, on December 23, 1895. He was reportedly deep in thought or reading while walking, failed to hear the approaching train, and was killed instantly. Some suggested suicide, which John denied.

Some of his fellow revolutionaries and supporters suspected that Russian secret police (the Okhrana) had arranged his death. The Tsarist regime had a documented history of hunting down political exiles abroad, and Stepniak was a high-profile revolutionary who had assassinated a top Russian official. The suspicious timing and circumstances led some to believe it was a carefully orchestrated assassination made to look like an accident.

The Arts and Crafts Republic

For the Yeats family, the ideals of the Arts and Crafts movement—its fusion of artistic expression, ethical design, and social reform—were not confined to England. They provided the blueprint for cultural renewal in Ireland. Inspired by William Morris’s utopian vision of a decentralised, cooperative society grounded in craftsmanship, the Yeats children sought to give material form to an Irish modernity rooted in its Gaelic past.

William Butler Yeats embraced these values in his poetic vision and personal life. The design of his Tower House in Ballylee reflected a conscious revival of medieval Irish architecture, combining national symbolism with the aesthetics of the Arts and Crafts movement. Furniture, textiles, and interior details echoed the simplicity and integrity of hand-crafted work, reinforcing his dream of a self-defined Irish culture independent of British models.

Wnen he had begun to write his first sucesses came with his turn to Irish folklore rather than the imitations o0f Englands lake poets. Under the strong influence of John O Leary. And his mothers longing to be back in Sligo.

“I would remember Sligo with tears, and when I began to write, it was there I hoped to find my audience”

His sisters, Susan (Lily) and Elizabeth (Lolly), gave practical embodiment to this vision. With training from May Morris and the Chiswick School of Art, they returned to Ireland and established the Dun Emer Guild and later the Cuala Press. These workshops specialised in embroidery, book design, and printing. Their work drew on Irish myths, folktales, and native ornament.

at the Froebel College in Bedford,publication of four popular painting manuals: Brushwork (1896), Brushwork studies of flowers, fruits and animals (1898), Brushwork copy book (1899), and Elementary brushwork studies (1900)

Jack B. Yeats, meanwhile, dedicated his art to depicting the West of Ireland—its people, landscapes, and customs. His impressionistic paintings and drawings gave visual life to the same rural world celebrated in his brother’s poetry. Unlike romanticised visions of the West, Jack’s work was informed by direct observation, empathy, and a democratic eye, illustrating scenes of ordinaryu life, from the dock workers in Sligo to the horse races on the beaches, his art documented a living tradition rather than a vanished one.

Together, the Yeats siblings imagined an Irish future built on the foundation of its own traditions—transformed, not abandoned, by modernity. The Arts and Crafts Republic they dreamed of was not nostalgic or backward-looking. Its roots were cosmopolitan, intellectually ambitious, and egalitarian. It aspired to give Ireland its own voice in the modern world—through art, through literature and through design.

By rooting Irish cultural identity in shared craftsmanship and creative independence, the Yeats family advanced a vision of national self-hood that was as political as it was artistic. In their work, the legacy of John Butler Yeats—the fusion of the Gaelic tradition and European radicalism lived on.

PART IV: THEORY INTO PRACTICE

Anarchist-Nationalism and “Irish Freedom“

How did these ideas manifest in Ireland?

The American anarchist Benjamin Tucker, in his 1897 work Instead of a Book, wrote admiringly of Ireland’s Land League:

“Ireland’s true order: the wonderful Land League, the nearest approach on a large scale, to perfect Anarchistic organization that the world has yet seen. An immense number of local groups scattered over large sections of two continents…each group autonomous; each composed of varying numbers of individuals…”

This fusion of anarchist radicalism with Ireland’s national struggle found further expression through successors of John O’Leary in the IRB, such as Bulmer Hobson and figures in the broader Gaelic revival. Standish O’Grady and George Russell (Æ), a close friend of W.B. Yeats, were instrumental in popularising the ideas of Peter Kropotkin in Ireland. While editing The Irish Homestead, Russell published essays by Kropotkin that advocated for voluntary association, decentralised communes, and mutual aid.

George Russell who was a close friend of WB Yeats, was publishing essays of Kroptkin while he was editor of The Irish Homestead.

O’Grady openly acknowledged the influence of Kropotkin, proposing an anarchistic programme of rural development and communal self-reliance. His writings appeared in The Peasant, Irish Ireland, The Irish Nation, The Irish Review, and The New Age—progressive periodicals that echoed the cooperative ethos of the Land League. The ideas circulating in these journals offered a vision of national regeneration grounded not in the state, but in community.

This was a conscious attempt to carry forward the fusion originally attempted by the Young Irelanders, who had combined Proudhon’s anarchism with Mazzini’s nationalist vision of self-determination. Now in a new generation, this tradition was updated through Kropotkin’s humane and practical philosophy and was developed in real-world terms through cooperative movements.

The Yeats sisters’ enterprises—Dun Emer Industries and Cuala Press—were organised as co-operatives. Countess Markievicz, in alliance with Hobson, attempted to establish cooperative businesses on her Sligo estates, though with limited success.

Alice Stopford Green (1847–1929) answered Thomas Davis’s call for a history of Ireland that was neither sectarian nor imperial but rooted in the dignity of its native civilisation. Not one focused solely on defeats and dispossession, but one that portrayed Gaelic civilisation as a dynamic and original culture.

She argued for this in works such as The Making of Ireland and its Undoing (1908), Irish Nationality (1911), and The Old Irish World (1912).

She wrote:

“No real history of Ireland has yet been written. When the true story is finally worked out… it will give us a noble and reconciling vision of Irish nationality.”

Alice Stopford Green

Stopford Green sought to document the material, social, and intellectual life of Ireland before conquest, aiming to inspire dignity and future independence. Sherejected the colonial narrative of decline and barbarism, instead portraying early Irish society as sophisticated, literate, and communally organised. Green bridged divides and offered a scholarly foundation for a pluralist, Gaelic-informed vision of Irish nationhood. Her histories aimed to restore pride, coherence, and cultural legitimacy to a people whose past had long been distorted or erased.

Her turn to the Irish cause had happened around the turn of the century, and it is perhaps not surprising that we find both O’Leary and Yeats as visitors to her house at theis time. John O’Leary, again sketched by John Butler Yeats in Alice Stopford Green’s London home around 1900, provides a tantalising link—from Young Ireland to the revolutionary intellectual circles of the early 20th century.

Her influence extended to James Connolly, who adopted her image of early Irish society as egalitarian and proto-socialist: “a socialist revolution in Ireland would be in certain respects a return to the early Gaelic system.”

“All valuable education,” John once wrote, “was but a stirring up of the emotions,” adding that true feeling was not excitability, but harmony: “In the completely emotional man, the least awakening of feeling is a harmony in which every chord of every feeling vibrates.”

This idea of deep emotional resonance as a guide to truth shaped his own life and that of his children. For John, genuine feeling was not sentimental outburst but the achievement of inner integration—a state where intellect, emotion, and moral conviction worked together seamlessly, creating what he called a “vibrating beingness.”

This conception of emotional harmony perfectly aligned with the revolutionary art theory emerging in 1880s Paris, where Georges Seurat was pioneering pointillism—a technique that would profoundly influence Pissarro and Signac. Seurat, trained at the École des Beaux-Arts but fascinated by the chemistry of vision, had discovered the work of Michel Eugène Chevreul, director of the historic Gobelins tapestry factory. Chevreul’s studies of “simultaneous contrast” showed that separate colors, when placed side by side, would blend optically in the viewer’s eye to create a third color—an effect he called “harmony.”

Seurat copied paragraphs from Chevreul’s treatises into his own notebooks, but he was most interested in how this optical harmony evoked emotion. His pointillist paintings—composed of thousands of separate colored dots—created what contemporary viewers described as “blurred vibration,” a shimmering atmosphere that seemed to reveal “all forms as a swarm of atoms, electric.” For Seurat, this visual manifestation of emotion as vibrating energy was the key to authentic artistic expression.

Just as Seurat’s paintings required active participation from viewers whose eyes completed the optical blending, John’s education required students to integrate their own emotional and intellectual capacities. Neither sought to dominate or manipulate, but rather to create conditions where natural harmony could emerge.

If separate colors could cooperate to create beauty, and separate emotional faculties could vibrate together to produce wisdom, then perhaps separate individuals could work together without coercive authority to create a just society. The “vibrating beingness” that John saw in fully developed humans was the same shimmering energy that Seurat captured in paint—both expressions of what happened when natural forces were allowed to find their own organic harmony.

He had no illusions about its material rewards. “It is impossible for a rich man’s son to enter the heaven of poetry,” he wrote. “Yet a poor man’s son should avoid poetry, because it is impossible to make money by the writing of poetry.” And still, he raised his eldest son to be a poet. “It was a secret between us,” he admitted, “I was not anxious to proclaim to the world that I, a poor man, was bringing up my eldest son to be a poet.”

It was in York Street, before he went to his regular studies, his father used to read poetry to the youth who was to become the greatest poet of our time. “ He never read me a passage because of its speculative interest, and indeed did not care at all for poetry where there was generalization or abstraction however impassioned.” Once he read from Coriolanus. “That scene is more vivid than the rest, and it is my father’s voice that I hear and not Irving’s or Benson’s.” The first poetry W.B. shows himself to us as writing is in the form of a play — “ a fable suggested by one of my father’s early designs. ”

This nurturing of poetry in the face of hardship illustrates a principle central to John Butler Yeats’s worldview: the pursuit of inner truth over material success. It echoed the ethos he recalled from his youth, when “the definition of a gentleman was a man not wholly occupied in getting on.”

Despite this, William Yeats eventually drifted into conservative and even authoritarian circles—something his father had tried hard to prevent. “He is naturally conservative,” John warned, “and I don’t want to see that side of his character developed. I would rather keep him in the ranks down among the poor soldiers fighting for sincerity and truth.”

In another letter, John dismissed the Nietzschean ideal of the Übermensch: “The men whom Nietzsche’s theory fits are only a sort of Yahoo great men. The struggle is how to get rid of them—they belong to the clumsy and brutal side of things.”

And so it was that William came to realise later in life that for all the effort he had made to move away from his fathers old fashioned ideas, startled himself “with some surprise how fully my philosophy of life has been inherited from you.”

This flow of energy and vision set the stage for the eventual Rising in 1916, an event that many of the IRB and others disagreed with (mainly because of its limited chance of military success). John himself referred to them as “mad fools”.

But the cultural thread of those who took part in the Rising was precisely that which we have outlined here. The IRB, now with Tom Clarke and MacDiarmada were a faction that had been brought in by Bulmer Hobson during his time as President. He was instrumental also in the founding of the Volunteers. Hobson, as we have seen was an eclectic socialist who was well versed in anarchist philosophy and political organisation.

The other main actor of the rebels was James Connolly, who of course history remembers as the great socialist thinker of the rebellion. His Citizen Army was organised by the anarchist Jack White. He himself had been an organiser for the syndicalist IWW in the US. The syndicalists were the union arm of the anarchist movement, and represented the most modern strain of anarchist thinking at the time, one in which the federated syndicates would replace the stste using the general strike to effect change. Connolly was co-opted into the IRB and forced to align his plans with theirs, but as weve seen , they represented merely older and newer forms of the same threads of radical traditions.

So these events are well studied and documented, but our concern here is how did the life and work of John Yeats, his family and his social circle feed into these events. Away from the military marches and the gunpowder and cordite of the militants, what was the other side of the revolution aiming at. And did they think they could effect change without resort to violence? And if so, how?

The Philosophy of Dreams

John, in a letter to his son, says,

“My dear Willie,” he once wrote, “I am afraid you must sometimes think me very conceited—the fact is not only am I an old man in a hurry, but all my life I have fancied myself just on the verge of discovering the primum mobile.”

‘My theory is that we are always dreaming – chairs, tables, women and children, our wives and sweethearts, the people in the streets, all in various ways and with various powers are the starting points of dreams … Sleep is the dreaming away from the facts and wakefulness is dreaming in close contact with the facts, and since facts excite our dreams and feed them we get as close as possible to the facts if we have the cunning and the genius of poignant feeling“

John Yeats, Private Letter to WB Yeats. Quoted in John McGahern, Trinity Quattrocentenial essay, in The Irish Times, 9 May 1992, “Weekend”, q.p.)

We could take this whimsically or mystically perhaps, but given what we know of Johns philosophy, we can assume he had a materialist basis for his theory.

The primum mobile (prime mover) was the outermost sphere in medieval cosmology that set all other celestial spheres in motion, but here Yeats uses it metaphorically to suggest he’s seeking the fundamental principle that animates all existence. This reveals his philosophical ambition: he’s not just developing an artistic theory but attempting to articulate nothing less than the basic mechanism of consciousness and reality.

“We are always dreaming” opens up profound implications for understanding how utopian idealism functions as a form of constructed reality. If consciousness fundamentally operates through dream-like processes of interpretation and projection, then utopian visions—whether anarchist, socialist, or otherwise—are not mere fantasies but alternative constructions of reality that possess both validity and transformative power.

This perspective anticipates modern neuroscientific understanding of the brain and its rol;e in constructing the reality we perceive. Making Yeats’s insight remarkably prescient. This isnt a relativist position either. The objective facts are always there. But humans access to them is always indirect, and the state of reality we perceive when waking is only somewhat closer to these facts than that when asleep.

William Butler Yeats grasped this principle and applied it to Irish culture. “I have desired, like every artist, to create a little world out of the beautiful, pleasant, and significant things of this marred and clumsy world, and to show in a vision something of the face of Ireland to any of my own people who would look where I bid them,” he wrote in The Celtic Twilight. This wasn’t literary romanticism but the practical application of his father’s theory.

His poetry demonstrated exactly what John meant by “dreaming in close contact with the facts.” When William wrote “Come away, O human child! / To the waters and the wild / With a faery, hand in hand, / For the world’s more full of weeping than you can understand,” he wasn’t describing an existing Ireland but constructing one. He gathered the “facts”—Irish folklore, landscape, language patterns—and used them as “starting points of dreams” for an alternative national future.

If all human experience is dreamlike, then what what prevents us organising things in a better way? It would mean that nothing is fixed as so many say “this is just how it is”. It would also mean that by changing the dream, we would change the reality.

This philosophy would have provided a profound foundation for believing that a better world could be actualized through artistic and political imagination. If consciousness is fundamentally “dreaming in close contact with the facts,” then the act of imagining alternative realities becomes not escapist fantasy but a legitimate mode of engaging with and reshaping the world.

This led to a very practical focus on the physical surroundings in which people lived. William Morris’s “craft socialism” represents a close parallel. Morris’s belief that transforming the conditions of labour and daily life could reshape human consciousness directly echoes Yeats’s emphasis on how “facts excite our dreams and feed them.”

Morris’s vision of beautiful, meaningful work wasn’t utopian fantasy but an attempt to materialize an alternative reality through immediate practice—and in this they created literally chairs and tables to create “the starting point of dreams”.

Susan and Elizabeth Yeats followed through on this philosophy by creating the Dun Emer Industries and the Cuala Press in Dublin. Here making manifest things dreamed by their poet brother, by printing editions of his books. These operated as co-operative enterprises, following the philosophy of the worker owned collective enterprises that the socialist philosophy sought to replace capitalist owned workplaces with. This also was in line with anarchist thinking that worked from the bottom up.